Index

Suriname in WW II

- Bauxite and the allied forces

- Aid for The Netherlands

- Internment camps (German missionaries and teachers, Internment of critics, Murders at Fort Zeelandia)

- Black outs, trenches and magazine clubs

- Visits from the House of Orange

- Jewish refugees

- (Para-)military (Gunners, City Guard, Country Guard and the KNIL, Women's Aid Corps and Women's KNIL Corps, Dutch Legion, Princess Irene Brigade, Marines, Militia, The liberation of Western Europe, The liberation of the Netherlands Indies, Employment against or with the Indonesian battle for freedom, Surinam veterans of war, Late recognition, Plaque Waterkant/Onafhankelijkheidsplein)

- War

- Youth

- Political activities

- Back to Suriname (January-May 1933)

- 'We slaves of Suriname' (1933-1934)

- Appearances and articles

- More about Anton de Kom

Hugo Pos

Twee militairen: Hugo Desire Ryhiner en Harry Frederik Voss

Other military men and women (A-Tjak, Alvarez, Balinge, Van Bazel, Burgzorg, Chateau, Van Eick, Emanuels, Gitz, Heidweiller, Van Helvert, Hilfman, Van der Hoogte, Huiswoud, Juta, Meijer, Netto, Del Prado, Salm, Spreeuw, Strauss, De Vries, Vrieze, Wesenhagen, Wiers, Wooter)

A group of marines from Suriname, the Netherlands Antilles and the Netherlands-Indies (Dissels, Kenson, Koulen, Kroes, Meeng, Van Meerveld, Menig, Van Niel, Renar, Wijngaarde, De Windt, Arloud)

Fallen in the Dutch Merchant Navy (van Aksel, Alie, Beeldstroo, Bijnaar, Boldewijn, Chateau, Colader, Cruden, Elmont, Emnes, van Exel, Flu, Gesser, Kerster, Klooster, Markiet, Mecidi, Moore, Muller, Naarendorp, Olff, Oostburg, Parisius, Pools, Rolador, de Rooy, Slagtand, Smiet, Stelk, Vrieze, Wikkeling, Woiski)

Names from the Resistance (Bijleveld, Bosschart, Does, Ezechiëls, Fernandes, P.C. Flu, H. Flu, Gitz, Jüdell, Kanteman, Lashley, Lichtveld, Lu-A-Si, C. van de Montel, van de Montel-Boeken, L.H. van de Montel, Nods, Nods-van der Lans, F. Rijk van Ommeren, H.N. Rijk van Ommeren, H. Rijk van Ommeren, L.H. Rijk van Ommeren, de la Parra, Rodriguez, M. Samson, Samson-Ezechiëls, P. Samson, A. Samson, Tolud, Wittenberg, Wolff)

Surinam jazz-musicians in The Netherlands (1940-1945) (Van Kleef, Johnson)

- The first years

- 'Barbaric'

- Enemy music

- Names

Sources / More reading

Suriname in WW II

Flag: nl.wikipedia.org

Map of Suriname, including disputed border territories

(source: www.suriname.nu - thanks to Mr. Lutz)

Bauxite and the allied forces

In 1916 the Aluminum Company of America (Alcoa) had bought the then known bauxite fields in Suriname – especially around Moengo, along the river Cottica. Bauxite is an ore which is used for the production of aluminium and therefore for building airplanes for example. Because of the War export increased. Not far from Paramaribo, in the district of Para, since 1938, along the Suriname River, Alcoa was preparing a new establishment. Between the company and the capitol the still existing, only 'highway' in Suriname was built. In February 1941 governor Kielstra opened the Paranam Factory (see www.alcoa.com). The Netherlands-Indies company Billiton also appeared. In 1943 Surinam mines provided 60% of the US need for bauxite. One year later though production in the US state of Arkansas started and the Surinam share diminished.

Bauxite mining in Moengo (picture: Bos & Van Palen, Illustrated Atlas)

The Surinam teacher of history Heinrich Ernst Helstone (1926-2010) explains how bauxite was transported. Because the Surinam river beds during those days were not deep enough, ships were only loaded for about 30-40%. From Moengo they proceeded, via the neighbouring Cottica and Commewijne Rivers, to the mouth of the Suriname River and on to Trinidad. There a second shipload was needed before the voyage to Mobile in the State of Alabama could start. Mobile was the North-American place of transfer. The crews of the ships were not Surinamese. Most of the crew were from British Guyana and Trinidad, officers were Norwegian etc.

After war's outbreak the United States did not want this strategic ore and the Alcoa installations to fall into enemy hands. That fear was very real. French-Guyana was controlled by the pro-German Vichy-government and there were many German immigrants in South America. Therefore president Roosevelt, on the 1st of September 1941, still before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor provoked the American declaration of war, offered Queen Wilhelmina to station 3,000 infantry and anti-aircraft defence troops in Suriname. The Dutch wartime government and governor Kielstra were surprised but had to accept the 'offer'. The military would formally be under Dutch supreme command and be funded by the Dutch. The first troops arrived on November 25, 1941. By year's end they numbered 1,000, and in 1943 over 2,000 soldiers. In September 1943 the US replaced the white troops by Puerto Ricans.

Entry US-troops, November 1941 (picture: www.verzetsmuseum.org)

Mr. E. Bleijert (1943) remembers a song of street singer Halfway. It went like this: 'Many Americans / were seen in those avenues / with their young ladies / walking side by side. / The finest was for sale / people were so crazy / about what that Yankee offered'. The latter didn't apply to everybody. According to Mr. C. Mehciz (1929) some people complained to the Americans about the condoms found on the streets on Sunday when they went to church. The churches organized a committee against moral decline. The complaints had little impact.

American presence had a liberating effect, economically and cultural. The black population was usually treated in an old-fashioned colonial way. The Netherlands had yet to implement the Atlantic Charter (9 August 1941), proclaiming the abolishment of colonialism after the war.

EBS-building, the American military home during the war

(picuture: www.verzetsmuseum.org / eigendom: Dagblad Suriname)

Until 1943, troops stationed in Suriname were white, but the men loved to have fun with Surinam teenage girls. At the current location of the Surinam energy company (EBS), there used to be the American military home, with the Stagedoor Cantine. This was one of the places of entertainment. Prostitution flourished. A month before the visit of the Dutch princess Juliana from Canada, territorial commander Meyer ordered a raid, at which 97 young men ('gang members') and 76 young women ('prostitutes') were arrested (7-8 October 1943). They were interned without any further investigation or trial until the end of 1944. One of the men, A. Oostwijk, was shot on 19 July 1944 after a (repeated) attempt to escape.

US-soldiers with Surinam girls (picture: www.verzetsmuseum.org)

Despite everything, the American soldiers brought life and a sense of the modern age to the neglected colony that now had been impoverished by the global economical crisis. Helstone, 15 years old at the time, recalls how their arrival in the harbour caused a sensation in town. Military ships unloaded modern trucks. With bulldozers they went for Mosquito Boiti in the Zorg en Hoop neighbourhood. They built barracks and a small airfield - which still exists. The small airport Zanderij, where in 1933 the first Dutch postal plane 'De Snip' had landed, was extended into a usable military basis and airfield. The road leading to it, the 'path of Wanica', was made suitable for trucks and tanks by covering it laterite, a bauxite-rich local soil.

To The Netherlands, Suriname had always been a 'money losing colony'. With a bit of luck individual slave owners, administrators of plantations and gold diggers could make a fortune, but the colonial government ('Lantie') was destitute and often asked the 'motherland' to plug holes in the budget. In 1935 the Dutch minister of Colonies, Colijn, lamented in parliament: "Everything that has been attempted in Suriname, it all simply failed." (http://home.iae.nl). In Suriname the following quote of Colijn is known: "Let's just inundate the colony".The 'East', the Netherlands Indies, on the contrary was very profitable and flourished. Young Surinamese signed up for six years work in the Indies as teachers. Others joined the Royal Netherlands-Indies Army (KNIL). In Suriname itself there was no perspective at all. Helstone remembers the exclamation 'teki konkomero', 'take a cucumber'. Together with a small case of clothes, a testimonial of good conduct and some money it constituted the travel luggage. People also moved to the United States, the Netherlands, Curaçao and Aruba, or mustered into ocean-going trade. In London, on the 7th of December 1942, Queen Wilhelmina held a speech, in which she promised self-government after the war to the Netherlands East-Indies, Suriname and Curaçao.

Aid for The Netherlands

Already from the beginning of the war money was raised in Suriname (and in the other colonies) for buying a fighter plane for the Allied efforts ('Spitfire-fund').

At the 5 May gathering 2008 in Amsterdam Zuid-Oost (CEC building), Mrs Stoffels and other elderly Surinam ladies told about the cent they had to bring to school every Monday morning. The song they sang at school went as follows:

'Children don't forget your Monday cent

Children don't forget

Whatever happens or will occur

Children don't forget your Monday cent.'

Initiated by J. Wijngaarde, journalist of the newspaper 'Suriname' 38.000 Surinam guilders were raised in 1940-1941. Philatelist Paul Daverschot for that matter believes it was 28.000 guilders and also mentions that this was just enough to buy 1 Spitfire. According to the website of the Verzetsmuseum the fighter, of course, was given the name 'Suriname'. Daverschot also writes about special postage stamps (Filatelie, October 2007).

Stamp aid campaign (source: Filatelie, October 2007).

Between 30 August and 31 December the Surinam postal services issued special stamps with surcharge, following the Netherlands-Indies. Proceeds went to the Prince Bernhard Fund, which bought with it Spitfires and other military goods for the Allies. The Verzetsmuseum (Resistance Museum) mentions on its website that the Fund in fact bought a destroyer, 'to replace the Van Galen, which was sunk during the May days of 1940'. (see: www.verzetsmuseum.org). Other gifts were made during and at the end of the war. After the liberation the first ship to leave for Amsterdam from Paramaribo carried aid goods from the Surinam population, mainly collected by women.

Gratitude monument Siva square (artist: Mari Andriessen)

(picture: Pim Ligtvoet, 2007).

In 1955 Queen Juliana unveiled a gratitude monument. Three girls represent the Creole (left) and Hindustani (right) Surinamese, who hold their arms around the back of the Dutch people (middle). The small heads on the pedestal represent the smaller ethnic groups of the country: Lebanese, Marron and Javanese. Native Surinamese and Chinese seem not to be there. The dedication on the back side reads: 'The Netherlands gratefully remember the aid during the years of war 1940-1945 and after that given by Suriname as a feeling of solidarity'.

Writer Cynthia McLeod, daughter of the last governor of Suriname, in her 'Memories: Suriname – war – Holland – Suriname' (1993) recalls the aid campaign. "Clothing, especially clothing. Not worn of course, oh no, which Surinam mother would send worn clothes to Holland? ... it had to be especially warm, so people bought flannel and sewed. Also the families who had to make ends meet gave ... and other things. Boxes full of peanut cookies, coconut cookies, gomma cookies were stuffed in crates and sent on, and don't forget the cocoa, our own, nutricious, homemade cocoa, that was just what those poor children in Holland needed to regain their strength. K"e Poti! Would they still remember? ... Ah, I think they already forgot a long time ago".

Internment camps

German missionaries and teachers

At the start of the war governor Kielstra had all male Germans past the age of fifteen imprisoned in Fort Zeelandia. Mr. Mehciz remembers this was announced through a 'proclamation'. The friar of his school explained the meaning of the word. The 'announcement by the authorities' implied that Holland was at war with Germany, and therefore Suriname as well. Thus the subjects of the German Reich in Suriname were considered enemies.

The proclamation of war (source: www.verzetsmuseum.org)

A week after their imprisonment in the small Zeelandia Fort, the about fifty men went to the Roman-Catholic mission boarding school at the Copieweg, 15 kilometres from town, along the railroad to Zanderij. Both the boarding school and railroad are now gone. House 'Melati' was built for children of Javan descent and housed about 200 students. After a while the German women and children were interned at the old plantations Mariënburg and Voorburg. In June 1941, behind the monastery at the Copieweg, twelve family barracks were readied, and the women and children moved in. Thus 134 people from German descent, six Surinam partners and three NSB'ers (members of the Dutch pro-German National Socialistic Movement) were detained.

Barrack at the present Copieweg (picture: Pim Ligtvoet, 2007)

Most prisoners were missionaries and teachers from the Evangelic Brother Community (EBG), known as 'Herrnhutters', and their families. They were held in great esteem by the population. Thanks to their efforts for the slaves in the nineteenth century, their church became the church for the Surinam Creoles. The 'mofo koranti', rumours among the people street, said some fanatic nazis were among them. In fact the Brother Community still was governed from Hernnhut in Germany, where count Von Zinzendorf founded the movement in the 18th century, but there appears not to have been any strong support for Hitler at all. In the Zeelandia Fort they were under guard of the white KNIL military billeted there.

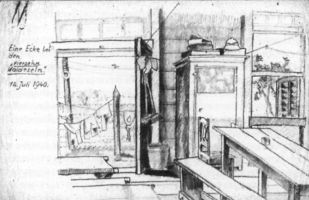

Barrack Copieweg, drawn by Aleander Gebhardt (July 1940) (picture: Wereldoorlog in de West, p.74)

The provision of bread in Paramaribo, strongly dependent on the large EBG-firm Kersten at the Domineestreet, came to a halt by the internment. Ever since their arrival in 1732, the Brother Community considered it their task, besides missionary work among Indians and inland Creoles, to earn their daily bread, so why not bake it yourself. Under the leadership of Christoph Kersten a factory was established at the Domineestreet, with a bakery where friar Heijdt and slave Primo ruled. In May 1940 the government seized Kersten & Co and changed it into a Limited Company. By happy chance two engineers from Wageningen, who had not manage to get back to Holland in time, De Kraker and Reitsma, were asked to run the company. According to Helstone they did this in an excellent way.

Detail EBG-column Domineestreet/Steenbakkerstreet (picture: Pim Ligtvoet, 2007)

Almong those interned was the crew of the German ship the 'Goslar'. This vessel already arrived in the Paramaribo harbour during the mobilisation (October 1939). Helstone, at that time at a German missionary school, remembers he liked talking to the Germans. Before the internment the crew, under great public interest, sank the ship, not far from the 'flat bridge', the ferry to Meerzorg. The wreck to this day belongs to the harbour panorama of Paramaribo.

Wreck 'Goslar' in front of Wijdenbosch bridge (picture: Pim Ligtvoet, 2007)

Sanitary conditions at the Copieweg and in Mariënburg were reasonable, but there were rumours about malaria and tetanus. The German Reich responded by taking prominent Dutch as hostages. Former Surinam governor dr. A. Rutgers was imprisoned in Buchenwald. In August 1941 three internees escaped: Alexander Schubert, Anton Boysken and Heinz Scharfenberg. Guarding was intensified but the treatment of prisoners stayed within the rules of the Geneva Convention.

After the war the German missionaries and teachers were expelled from Suriname. Thousands of Surinam citizens, dressed in white as a sign of mourning, accompanied their departure from the Copieweg to the KNSM-landing stage in Paramaribo. According to Heinrich Helstone the driving force behind this expulsion was not only the colonial Dutch government. The Dutch branch of EBG, in Zeist, rather wanted German supervision over EBG to disappear. And in Suriname there were non-German missionairies like the Danish Hans Peter Jensen, his fellow Danish Legêne and the Swiss Raillard, who promoted the departure of their brothers in faith.

The group of men, women and children proceeded with the later troop ship ss Bloemfontein to Curaçao, where other Germans were picked up. In Holland they were interned in Mariënbosch near Nijmegen and from there they spread over the different zones of post-war Germany. As Helstone recalls, some of the missionaries stayed in Suriname. The Swiss consul A. Gonzenbach visited the Surinam camps during the war as a solicitor for the German subjects. Through his mediation some could migrate in 1945, at their own request, to Venezuela. One of them was called Zickmantel.

Internment of critics

Otto Huiswoud (picture: www.suriname.nu)

During the first years of war governor Johannes Coenraad Kielstra had also 177 left wing revolutionaries, nationalists and other opponents arrested. One of the most famous was Otto Eduard Gerardus Majella Huiswoud (1893), interned in January 1941. Huiswoud, who in 1910 migrated to the United States, was the only black among the founders of the American Communist Party. He had been active as a 'Komintern'-man, international propagandist. After a kidney operation he left the United States on 15 January 1941 for his country of birth. The captain of his ship, the ss Pygmalion, informed the harbour police, who arrested the passenger and interned him at the Copieweg. There Huiswoud protested against the combined detainment of nazis and anti-fascists, German Jews and missionaries. The protest was successfull: the nazis were henceforth detained separately. During his over eighteen months of imprisonment Otto Huiswoud made a good impression on the attorney general, and people like Bos Verschuur (who had been elected into the State Council in April 1942) constantly pleaded for his release.

After a meeting in 1942 in New York between his lawyer Stevens and the governor, Huiswoud was freed in October 1942 after signing a declaration of non-activity. Otto lived with a daughter from his sister and was held under a kind of house arrest. In 1947 he moved to Amsterdam with wife Hermine Dumont (see: Maria Gertrudis Cijntje-van Enckevort, The life and work of Otto Huiswoud, diss. 2003).

W. Bos Verschuur, late 1920 (picture: www.leoglans.nl)

Probably the most famous prisoner of the Copieweg was Wim Bos Verschuur, artist, teacher, politician ('Being our own boss'), union man, member of the State Council and indefatigable critic of the governor. He published the newspapers 'Waakt' ('Vigilance') and 'De Zweep' ('The Whip'). In 1943 he drafted a petition for the London-based Cabinet of War, to get the governor fired because of his supposedly pro-German sympathies. Kielstra then had Bos Verschuur detained at the Copieweg, separately from the Germans. He refused to give any explanation for this to the State Council, upon which seven of the ten elected members of the Council decided to resign. Young admirers of Bos Verschuur demonstrated and were also arrested. The colonial elite feared an uprising and informed London accordingly.

Governor J.C. Kielstra (picture: www.verzetsmuseum.org)

Kielstra was honourably dismissed early January 1944 and had to move to Mexico. The actions for release continued and in October 1944 the new governor, J.C. Brons, had 'uncle Wim' set free - though he had to refrain himself from political activities. Bos Verschuur was knighted in 1947.

Heinrich Helstone had drawing lessons by Bos Verschuur at the Zinzendorf school. He didn't learn to draw all that much, young Heinrich wasn't very gifted, but that wasn't the only reason. Verschuur continuously spoke about the many things that occupied his mind. Among them the design of a new type of shoe, the performance of football clubs like 'Forward' and 'Cicerone', and his peculiar slogan for the State elections of 1942: 'Don't vote for a bushes man but for Bos 'ur man.' Mr. Bleijert also followed Bos Verschuur's lessons and was very much inspired by him. He remembers people waving from the train to the prominent prisoner at the Copieweg.

More on Otto Huiswoud, Wim Bos Verschuur and other interned at www.suriname.nu

Right after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor (December 1941) 146 residents in two penal camps on Java, Netherlands-Indies, were interned in Suriname. Most of them had German surnames and were, rightfully or not, arrested on charge of membership in the East-Indian National Socialist Party. Among them was a second cousin of the Dutch writer Multatuli, dr. E.F.E. Douwes Dekker, who fought colonialism, and there were supporters of the later 'Father of the Fatherland' Soekarno. On 21 Januari 1942 they were assembled in a big steel cage aboard the ss Tjisadane. Around the cage explosives were installed. Should the ship be attacked, the prisoners would be eliminated by igniting the explosives from the lifeboats. The ship however arrived unharmed on the 21st of March 1942 (see www.wikipedia.org, www.nationaalarchief.nl and www.prinsesirenebrigade.nl). A similar transport from Sumatra to the British Indies was hit by Japanese bombs almost immediately after departure. The 472 Germans interned were abandoned on the slowly sinking ss Van Imhoff (see Netherlands Indies - homosexuals). After a stay in Fort Nieuw-Amsterdam and Fort Zeelandia the prisoners from the Indies were transferred to the former inland plantation Joden Savanne. During the summer of 1942 they were kept together with some conscientious objectors from South-Africa. The conditions in 'the green hell' were degrading. Initially surveillance was done by the marines. One of the so called militiamen who worked there, Max Valdink, about the guards: 'They were pure criminals'.

Guno Hoen (1922-2010), sports journalist and former militiaman, with veterans badge

(picture: Pim Ligtvoet, 2007)

Another militia man, corporal Guno Hoen (1920), said the only thing they did was standing on guard. Prisoners would warn them when they dozed off. "Then they shouted: there's the commander!". After some time the militia men were given leadership, which meant a real improvement. Mr. Mehciz also remembers a song the conscripts sang when they marched into town: 'At Joden Savanne / there are no girls / send me back / to my dear Paramaribo'.

Murders at Fort Zeelandia

Late 1942 some prisoners had to clean the guards toilets with their bare hands. After they refused they were confined in a remote wooden cells barrack. The decided to escape during the night of 4 - 5 November. The plan was thought up by the later cartoonist Lo Hartog van Banda (1916-2006), who was released on the 4th of November because of his birthday. The other four escaped without him, after having sawed a plank out of the back cell. They were caught and interrogated by the military and territorial commander Johan Kroese Meyer in Paramaribo at Fort Zeelandia, and sentenced to death. While being returned to their cells, two of them were shot at close range, because of suspicous movements (6 November 1942). They were L.A.J. van Poelje and engineer L.K.A. Raedt van Oldenbarneveldt. With the other two, C.J. Kraak and KNIL soldier Stulemeijer the disguised execution failed. The latter put out the word that they refused to open Jewish graves to search for jewelry (www.wikipedia.org). In May 1943 J.K. Meyer was transferred by the London government (because of something completely unrelated) and was made commander of the ground forces in Australia from July 1943 until August 1945. There, in 1944, the Surinam volunteers would come in. The group of internees from the Indies ended their imprisonment in the social club Halikebe, nowadays hotel Torarica. Only in July 1946 they were released, without any form of trial. They received a compensation of 500 guilders.

J.K. Meyer (picture: www.verzetsmuseum.org)

J.K. Meyer was never prosecuted for the double murder. In 1948 he was promoted from major to general major and for his battle against the nationalists in Indonesia he received the Military Willems Order. He established himself in United States where he received the Legion of Merit, in the rarely granted officers class. The attorney general of Suriname, Grünberg, performed an in situ investigation in 1949. His report disappeared. The Netherlands concluded in 1950 that 'crimes' were committed, but dropped the subject. In 1994 minister Voorhoeve (sort of) apologised to attorney A.G. Besier of the relatives.

Sources:

www.onderscheidingen.nl (look at Decorati for Meijer)

NRC, 17 November 2006, 'The camp overseas' about: Twan van de Brand: 'The Penal Colony. A Dutch concentration camp in Suriname'. Balans 2006.

www.suriname.nu

Interviews by Pim Ligtvoet wit Heinrich Helstone, C. Mehciz and E. Bleijert, Paramaribo 2007

Black outs, trenches and magazine clubs

Because the government was expecting bombers - though no German or Japanese planes were ever seen - from a certain date during the war all lights had to be out during the night (globally between 7 and 7 o'clock). These were the black outs. Homework was done at candle light. The very common gas lights and rare electrical bulbs were put out or were wrapped in material like kite paper and textile. Young Helstone helped the already older teacher Annie Groenewegen with this kind of 'blackening'. Bicycles with lights on were suddenly prohibited. Kielstra even was preparing for an attack or battle in town. In several places 'trenches' were dug out. Mr. C. Mehciz (1929) explaines these were actually hide outs between two wooden walls where on the left and the right of it sand had been dumped. They were built on the axis of some major roads, like the Dr. Sophie Redmondstreet, the Waaldijkstreet and the Hofstreet, in the neighbourhood of Ondro Bon. Traffic was hardly obstructed because at that time there were only about 50 cars in Suriname. Everyone knew all the plates, including their owners. Under the leadership of one of the now extensive military groups, exercises were held per neighbourhood. After a triple sirene of three signals citizens were to proceed to the nearest trench. There they stayed for until the signal 'clear' was given. The government and the military commander clearly overestimated the possibilities of the Germans in South America, and after a while the exercises stopped.

Annoying during the war was that almost nothing came from Holland anymore, not even reading matter. Schoolboy Helstone therefore founded an American magazine club, with magazines like Time, Look and Life.

Visits from the House of Orange

Suriname and the Antilles where the only parts of the Kingdom not occupied by Germany or Japan.

Princess Juliana at the Red Cross in Paramaribo, November 1943

(Source: www.npogeschiedenis.nl, Feb. 2008)

Prince Bernhard

In October 1942 Prince Bernhard was the first member of the Royal Family in a hundred years to travel from London to Curaçao, Aruba and Suriname. The prince visited on the 24th of October the oil refinery of Aruba and flew on to Suriname. There he stayed from 26 - 28 October. He visited the Higher German Synagogue (27 October) and the bauxite mines

Plaque Higher German Synagogue as a remembrance to the royal visit

(picture: Pim Ligtvoet, 2007).

Princess Juliana

In 1943, from Canada, princess Juliana followed. From 2 - 9 November 1943 she was in Surinam. Earlier her plane flew over Saint Eustatius and Saba (see chapter of Antilles). In Surinam princess Juliana visited the cantine of the Militia where she also met the Womens Voluntary Aid Corps. She also visited the women of the Red Cross. In the district of Commewijne she was received by enthusiastic delegations from maroons. At Paranam she visited the bauxite company Alcoa. See the film on www.npogeschiedenis.nl/speler.program.7075663.html

Puertoricans

Welcoming parade at the Gouvernementsquare, Paramaribo

(Source: www.npogeschiedenis.nl/speler.program.7075663.html).

The US-troops which were in the welcoming parade for the princess were almost entirely made up of Puertoricans at the time. One of them was Manuel Rey Gonzalez. From October 1943 until July 1944 Gonzalez was captain of the Military Police in Paranam (e-mails Mrs. Connie Everhart and Nelida Frontéra, Oct-Nov. 2014).

Jewish refugees

Students from the school for Jewish refugees.

(Picture: Wereldoorlog in de West, p. 115).

Right from the start of the colonization, there had been Jews in Suriname. There was a Portuguese and a Higher German Community which in 1940 together numbered about a thousand persons. Traditionally they were part of the white (and mixed) elite. In 1890 for instance, half of the members of the States of Suriname were Jews. Even so, from the end of the 18th century on, their position in society declined. This is shown in the dissertation of Wieke Vink, 'Creole Jews, Negotiating Community in Colonial Suriname'(11 September 2008). Dr. Vink concludes that, during the late 18th and early 19th century, the Surinam Jewish community changed from a social-economical elite with a separate legal status, into a increasingly marginalised religious community. As a religious-ethnic group they constantly had to negotiate about there position in the colonial balance of power (Source: De Ware Tijd, 17 September 2008). Plans by the United States and by the Jewish Colonization Society in the late thirties to let European Jews emigrate to overseas territories of the European countries, like to the Saramacca-area in Suriname, were considered too expensive by the Dutch governors in the Antilles and Suriname. They were supported on this by the Jewish community itself, though they might be prepared to admit wealthy Jews.

Adelaar-Fürth family, around 1938. Standing from left: Willy (Wilhelm Meijer), Freddy (Frederika Sophie) and surviving son Ernst Henri; sitting Eduard and Else (Elisabeth)

(Source: www.joodsmonument.nl).

This however failed to keep some impecunious Dutch Jews from coming to Suriname just before or early during the war. Ernst Henri Adelaar (Deventer, ca. 1911) was the only one of the Adelaar-Fürth family to survive the Shoah by settling in Suriname in 1939. His parents had a drapery business in Deventer; there were two more adult children. After the war Ernst Adelaar married Sara Ruth Aptroot (London, 1913). The couple had two children and at least four grandchildren. The wife and two children from the originally Polish Arie Lew (Leo[n]) Pajgin (Grodno, 1888) from The Hague, managed to escape to Suriname after his death in 1941 (Source: Joods Monument).

As soon as the war broke out, the two Jewish congregations brought their valuables to safety outside the synagogues. Among the interned of May 1940 there were seven Jews with a German or Austrian background. War progress was followed very closely and, unlike Holland, the first deportation of Dutch Jews on 15 July 1942 was taken very seriously. One month later, on the 15th of August, the two synagogues held a combined service, followed by a demonstration the day after.

On the 2nd of December 1942, the Christian churches (EBG, Lutherian, Roman Catholic and Dutch Protestant) prayed for the 'suffering people of Israël' and on Friday 11 December a special service was held by the moslim community, which was attended by Jewish representatives. The Central Committee on Jewish Interests in Suriname, then organized on the 30th of December a protest meeting in the Bellevue Theatre against the 'complete extermination of Jews in the occupied countries'. The chairman of parliament spoke and a speech by the governor was read. The Committee did not pick this day randomly. It followed an appeal by the Palestine Higher Rabbinate after Hitler ordered the extermination all Jews in occupied Europe by 31 December 1942. On the 1st of July 1943, when it was assumed the last deportation from the Netherlands was completed (the last trains actually rode in September 1944 - ed.), a day of mourning was held.

The ss Nyassa (picture: pensarnaodoiaiai.blogspot.com).

Mid 1942 the Dutch War Government asked Suriname to admit a thousand Jewish refugees from Vichy-France who were threatened with deportation. The governor and States consented, but first wanted to arrange housing for the refugees. Before it was finished Hitler put an end to the independence of the Vichy-government. On 24 December 1942, 123 refugees from Portugal arrived with the Nyassa. On the 5th of January 1943, 55 others from Jamaica with the ss Cottica of the Dutch KNSM. Those aboard the Nyassa were diamond traders who lived in Antwerp in 1940 and managed to flee via France and Spain to neutral Portugal. The group was met with a warm welcome, first in the Chinese society Kong Njie Tong at the Steenbakkersgracht (nowadays Dr. Sophie Redmondstreet). In October 1943 they were able to move to housing built on the former cemetery Jacobusrust. Children attended their own school.

Kong Ngie Tong-society, 2006 (picture: www.nospang.com)

After the war the Parliamentary Inquiry (1951) was harsh on the dismissive attitude of the governors in the West. Many more Jews could have been taken in. For a list of Jews, mostly born in Paramaribo, who died in the Holocaust and the war in general, see the separate paragraph on Surinam Jews.

(Para-)Military

Militia, City Guard, Country Guard and the KNIL

In 1942 the colonial gouvernment set up a form of military service based on the already (since 1939) existing voluntary 'Militia' in Suriname. It applied to men between 18 and 43 years and at first was met with little enthusiasm. Eventually the corps in Suriname would number 5,000 men.

Historian Helstone ascribes the interest to the pressure of the economical crisis under governor Kielstra on the ordinary man and woman. Military service provided an income that, be it low (2 - 2.5 guilders a week), still was a regular income. One was also provided with a uniform, a gun and a military cap, and one could make promotion. Medical checkups held in the Country Hospital went on for days. The doctors tested blood for malaria and filaria (elefantiasis). 30% of the recruits were dismissed. Overall hygiene was poor. Many people in town still lived in the old slave houses in the backyards of middle class houses, 'yard-houses', where the 'kalaka skotu', the cockroach police, every now and then cleaned up. Only the water supply was reasonable. The better-off families had running water, the others could at least use the tap in the yard and on the street. The water quality was (and is) so good, that it surprised the Americans. The approved recruits were quartered in Zeelandia and on a field at the Gemenelandsweg, Hindus were housed in a building from 'Coco' Nassy. The Militiamen exercised on the Orange square (nowadays the Independence Square) and drove around in jeeps. They guarded Paramaribo, the border districts Albina and Nickerie, the bauxite mines and bauxite transport.

In 1940 Mr. Mehciz lived in the Wagenwegstreet across the Oranje School. This, just like the Selecta School in the Heerenstreet, Court Charity at the Burenstraat, and a terrain at the back of the Country Hospital, was appropriated as military quarters. He heard the trumpeteer play the reveille. After getting up the roll was called and the ill and punished were mentioned. The children sang songs along with the trumpet: 'the doctor's here / the doctor's here / the doctor's HERE'. And also 'Are there more punished / then they report to the guard / they must get out / they must get out'. There was a working schedule, with a separate one for the punished. Mr Mehciz remembers the conscripts sometimes practised at the firing range in the Cultuurtuin. They were also put to work at construction projects like the road between Albina and Moenga and the section between Paramaribo and the Saramacca River ('the garrison path').

In order to get enough schools to serve as barracks for the Militia, the government reduced the number of students, Mr. Mehciz recounts. Because there was no free higher education in Suriname after high school, many students just kept coming. They still tried to get their diplomas or to pick up some further education. Now, every student reaching 18, had to leave school. Boys became conscripts straight away. Young teachers and doctors were also called up. At the de-mobilisation of 1945, 23-year old soldiers without a diploma, were sometimes sent back to school. Others found a job despite lacking a diploma. And some tried to join the Dutch army. That was not simple for they hardly had had any military training during their service in Suriname.

The City and Country Guard (m/f) lines up (picture: www.verzetsmuseum.org).

A voluntary part of the Militia was formed by the 'City and Country Guards'. They patrolled the border with French Guyana and remote areas and were to report possible spies.

Women also served at the City and Country Guard, the Women's Voluntary Aid Corps (300 women), with commander L. Stahel-Jordi. They worked at the Harbour Office, the Transport in the Tropics, the Telephone Company or a storehouse, but also learned to shoot and exercise. They were drilled by the marines and were quartered in the Cultuurtuin (the 'Kul'). Heinrich Helstone remembers that the women's unit, shortened as BBM, also was translated to mean 'Bigi Bille' of 'Bigi Bobi' Girls. They wore non-traditional clothes like trousers and overalls. To the women it was a pleasant time, with a lot of community sense and a reasonable income.

Also in the 'West' a unit of the Royal Netherlands Indies Army (KNIL) was stationed; in May 1940 there were 200 KNIL soldiers in Suriname. They were head quartered at fort Zeelandia. A well-known Dutch Surinam KNIL-man was captain Hugo Desiré Ryhiner (see paragraph 3 Military). Helstone remembers a few of the names from Surinam KNIL soldiers: Latour, Getrouw and Netto (see Other Military men and women). They had a nice uniform and a regular income. KNIL men from the Indies also served in Suriname. They were known as 'liplappers'.

Womens Aid Corps and Womens KNIL Corps

Een van de vrouwenkorpsen (picture: www.verzetsmuseum.org).

A small group of Surinam women were also in military service. Some belonged to the group of 37 volunteers of the Womens Aid Corps who left in September 1944 from the US, the Antilles and Suriname for England. Among them was the trained nurse lieutenant Anne van Trikt, the civil servant Ro Wildschut, Anita Zorgvol, Annie Hiemcke, Carmen Goede and Jeanne Stifft (www.suriname.nu). In England they nursed wounded soldiers, in Belgium and the southern Netherlands they attended to the wounded and other injured, and after the war they worked in the Buiten Gasthuis for the starved Amsterdam population. Other women entered service, mainly as nurses, in the Women's KNIL Corps. Among them was teacher Theophilia Berkenveld who worked at the office of the marine intelligence. 'We found out we were also there to amuse the men. They couldn't shoot all of the time... The soldiers needed girls to dance with' (also see section 'Verhalen' (Stories) on this site).

Dutch Legion, Princess Irene Brigade

Already in August 1940 the exiled Dutch government conscripted all Dutch men between 19 and 36 years of age in the 'free' parts of the world to join the service in a 'Dutch Legion'. Only a few recruits were taken in. That was unsuccesful, but not in Suriname.

Appeal for volunteers (picture: www.verzetsmuseum.org).

In summer 1941 Hugo Pos attracted 400, mostly creoles, as volunteers for the Dutch Legion. They were refused though, for fear of tensions, which might arise between them and South-African volunteers. In August 1941 the Royal Dutch Brigade, already training in England for several months, was given the name of princess Irene. The later territorial commander J. Kroese Meyer, a KNIL major, was staff officer. Prime minister Gerbrandy also did not want any 'little niggers in the Irene Brigade' (Minister Council 1 juli 1944), but despite of this about 15 Surinamese joined the brigade. They were especially active in the liberation of Europe (see below). This also applies to a group of 9 Surinamese men who in their search for a job started working in Curaçao and then signed up with the marines - see the paragraph about them between 'Other military' and 'Sea Farers of the Dutch merchant navy'. The Princess Irene Brigade had a Dutch detachment in Paramaribo. They were quartered in the Selecta school in the Burenstreet. The troops formed, together with the Dutch marines, the staff of the Militia. The were held in low regard though by the Militia. Black military could not have promotions and were, by some of the men from the Irene Brigade, beaten all too easily.

Apart from the Surinam and Dutch units and the 2.000-plus US-military, there was also a group of marines from the Netherlands Indies, who had traveled as guards with the earlier mentioned 146 critics from the Netherlands Indies. A small number of Surinamese worked as naval men to protect the harbour. The military and para-military groups brought a garrison character to the capital.

'Gunners'

Gunner (picture: www.verzetsmuseum.org).

After the occupation of the Netherlands-Indies by Japan early 1942, the government appealed directly to young Surinam men to join the fleet. About 200 volunteers reported as 'gunners' on merchant ships or to guard the Paramaribo harbour. Jacques Marius Lemmer sailed three years as a gunners commander on the ship Fort Orange. It transported, in convoy, arms, ammunition and food to the allied forces in Europe. The work on board was dangerous, the working conditions miserable and initially food only consisted of potatoes, no rice. Hugo Pos* also was a gunner for some time, on the 'Flora'. During the war 48 ships from the KNSM (Royal Dutch Shipping Company) were sunk; as a result 247 crew lost their lives. The plaque at the Waterkant lists 29 names of sailors, most of them from gunners (see below).

Liberation of Western-Europe

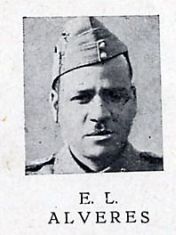

During the invasion of Normandy the Princess Irene Brigade was put ashore as part of the British army in augustus 1944. Part of this Brigade were the Surinamese Willy Wooter, Henri van Helvert and Leo Alvarez. They fought as paratroopers against a.o. German child soldiers. On Dutch soil the brigade took part in the liberation of areas around Tilburg and Hedel. Corporal Leo Alvarez was hit in the head at Oirschot by grenade shrapnel and died on 27 October 1944. A bullet grazed Willy Wooters neck at the Waal bridge, and Henri van Helvert lost a leg in the attack on a German machine-gun nest. The name Alvarez appears on the plaque at the Waterkant (see below and at 'Other military men and women').

The liberation of the Netherlands-Indies

Camp Casino Australia (picture: www.verzetsmuseum.org).

KNIL-military from Suriname and the Antilles were deployed against Japan from the Netherlands Indies. Many of them were made prisoner of war. The highest decorated Surinam-Dutch military, KNIL sergeant Harry Voss, was shot in Sumatra in May 1943. Another KNIL soldier died in Thailand in the fall of 1943, during labour at the notorious Burma Railroad. Nine military died in September 1944 on board of the Junyo Maru, a ship that was used by the Japanese for the transport of prisoners of war, but with no markings as such. Among them was Bert Huiswoud, brother of the Surinam revolutionary Otto Huiswoud. Other Surinamese worked for the navy. In the spring of 1942 a Surinam navy pilot crashed at the coast of Borneo, near Balikpapan, and another navy pilot died shortly after the war in Djakarta (during the Bersiap period) - see the paragraph Other military men and women. 15 fallen soldiers are listed on the war monument at the Waterkant in Paramaribo.

For the battle against the Japanese the 'pre-war' KNIL military were augmented by hundreds of volunteers. They came from 'the West' or were mobilised Dutch from non-occupied territories and Papuas from New Guinea. Surinamese and Antillian could only be sent to the battlefields of Europe and Asia on a voluntary basis. The Surinam States refused to change the constitution to permit compulsory service abroad. In 1943 between 150 and 200 volunteers responded to the recruiting campaigns of the KNIL and the Royal Navy. Most went to the Netherlands Indies. At the end of 1944 three detachments of volunteers went to Australia, about 450 recrutes. They were incorporated in the front forces. The Dutch ground commander was J.K. Meyer (see above) who had been 'kicked upstairs' from Suriname.

Australia was not exactly a paradise for non-whites. At the time it very much resembled the South Africa of apartheid. Two Surinam-Dutch companies fought in New Guinea (January 1945) and in Borneo (May-July 1945) in an Australian 50,000 men strong army. In New Guinea they had to track down the Japanese in the jungle. In Borneo, together with Australian and English troops, they recaptured the oil harbours of Tarakan and Balikpapan. Six Surinam KNIL volunteers were killed. Their names are unknown. Originally the war monument at the Waterkant in Paramaribo was dedicated to the fallen Surinam volunteers.

War monument Suriname. In the background the current presidential palace. This monument was, according to the inscription, initially dedicated to the 'Surinam volunteers of war 1944-1947'. Thus partially to those who were deployed in the liberation and re-colonization of Indonesia (picture: Pim Ligtvoet, 2007).

Employment against or with the Indonesian battle for freedom

After the capitulation of Japan general Mountbatten did not want any Dutch troups on Java. Despite of this in October 1945 some KNIL-companies went. Surinamese taking part in this, sometimes got into a moral dilemma. In those days jurist Hugo Pos, who in 1941 escaped occupied Holland, worked for the Dutch Legion recruiting agency in Canada and Suriname, and served as a gunner on a merchant ship, at the time working for Netherlands Indies Civil Administration. He was used to see Germans, Japanese and everyone who supported them, as the enemy. 'When the Indonesian revolution broke out this pattern completely changed'. To save their own lives KNIL men fired at nationalists.

Military Semmoh: ' ...only later on we realised how crazy it was for one colony, trying to loosen its ties, to oppress the other one'. He once surrounded a group from which a man called: 'Don't shoot, I'm Surinamese'. Still he got shot. William Watson refused to fire at nationalists: 'In Suriname you had neighbours from Java. I didn't want to fight my neighbour. That's it'. Watson knows about one Surinamese for sure, to defect deliberately. 'His name was Esseboom. He must be living there now, just like a Surinamese Poncke Princen'.

In late 1946 Surinam soldiers were sent to Holland, there were enough white men and volunteers in service. They were awaited by armed MP's and transported to the KNIL-depot in Kijkduin. In February 1947 the group arrived in Paramaribo. After initial enthusiasm they were given a nasty look: often they could not find jobs and they were blamed for being in the battle against Indonesian nationalists. Some veterans served again in Indonesia or Korea. In 1961 an urn with soil from the Korean war cemetery Tanggok was placed at the War Monument at the Waterkant. Later on the Korean community of Suriname erected a memorial in honour of two fallen men in Korea J.W. Bandison and H.G. Seedorf at the other side of the monument.

Surinam veterans of war

In the Weekly paper of Suriname (22 May 2003) Surinam ex-military Fred van Russel confirms the above specifications. The former union leader is chairman of the Federation of Veterans and Ex-military. He estimates during WW II about 200 Surinam soldiers have died in battle. About the contribution of women he says: 'Fifteen Surinam women served in the KNIL as nurses and another eight went via England to [by now freed parts of] Belgium and the Netherlands'.

Late recognition

Van Russel fights with about 70 other surviving Surinam veterans for payment of non-received allowances and pay and for compensations which were given to veterans with a Dutch passport. In July 2003 allowances were given to 580 Surinam veterans. One could also obtain a war veterans pass and a medal.

Earlier, after a protest march of 'Recreation for Surinam Veterans of War' (ROS) in which a big hole was cut out of the Dutch flag (1985), the veterans and the Surinam ambassador were also invited to the National Remembrance Day at the Dam in Holland. Veteran Semmoh: 'When we tell we as Surinams also fought in the Second World War we are only met with disbelief'.

Plaque Waterkant/Independence Square

Plaque on the war monument in Paramaribo (picture: Volkert Laurens Laan)

On the 4th of May 2006 the Surinam authorities unveiled a plaque with 63 names from the Second World War. The plaque was attached to the existing war monument at the Waterkant/Independence Square. President Venetiaan was unable to attend the ceremony. But the American ambassador was there. The plaque was too small for all known names. Therefore it was decided to take four categories with a limited number of names: military men (13), resistance fighters in Holland (11/12), Jewish victims (10) and sailors (29). A small plate with 9 names of military and resistance fighters presumably was mounted on the side of the monument later on. All names are also on the monument, except for Waldemar Hugo Nods. About him and the other fallen military, resistance fighters and Jews, more information can be found in the paragraphs Anton de Kom, Harry Frederik Voss, Other military, Fallen sailors from the merchant navy, Names from the resistance and Surinam Jews.

Below are the names on the plaque in 2006. Those who are also on the added plate have a (2) added.

Fallen military (13)

Harry J. van Bazel

Leo L. van Eick

Albertus C. Heidweiller

Egbert J. Huiswoud

Johan F. Netto

Desire G. del Prado*

Willem A. Spreeuw

Willem Meijer

Hendrik J. Wiers

Harry Vos*

Leo Alvares* (2)

Willem M. Burgzorg*

Eddy H(erman) Chateau (2)

Fallen resistance fighters in Holland (11/12)

Samuel F. Abraham*

Frank Rijk van Ommeren

Lodewijk H. Rijk van Ommeren

Jozef N. Rodriquez* (2)

Charles D(esiré) Lu-A-Si (2)

Iwan H. Kanteman

Anne D. Bosschart*

Henry H(ans) Flu (2)

Albert Wittenberg (2)

Anton de Kom (2)

Nicolaas W(alter) Gitz (2)

Abraham S. Fernandes*

Surinam Jews murdered and killed by gassing (10)

Elina Bueno de Mesquita-da Costa

Rebecca Fernandes-Swijt

Daniël E. Gomperts

Bernard Israël Levie

Hartog J. Pos

Flora M. Samson

Rozette Levie

Julia M. Bueno Bibaz

Rachel Martha Polak

Rosetje Bramson-Samuels

Seafarers, fallen by torpedoes (29)

A.J.H. Askel*

C.E.L. Boldewijn

H.H.W. Gesser

H.W.M. Kerster

A.W.I. Naardendorp*

A.C.A. Parisius

E.A.J. Stelk

J.D.L. Wikkeling*

M.P. Bijnaar

W.H. Beelds*

J.D. Cruden

C.L. Emnes

H.H. van Exel

E.G. Muller

J.E. Markiet

R.R. Oostburg

J.A. Olff

W.M. Pools

F.F. de Rooy

R.C. Colader*

H.A. Slagtand

M. Elmont

I.P. Flu*

E.M. Klooster

A.J. Mecidi

E.E. Moore

L.E. Smiet

W.A. Vrieze

A.G. Woisky

A. Alie

P.S.: The summary on the plaque is a selection. Also not all Jews died of gassing. Nor did all sailors die of torpedoes.

The spelling of some names differs* from the spelling by the War Graves Foundation (www.ogs.nl) and the Amsterdam KNSM monument:

- With www.ogs.nl:

A.J.H. Askel: van Axel

R.C. Colader: Rolador

Desire G. del Prado: Desiré

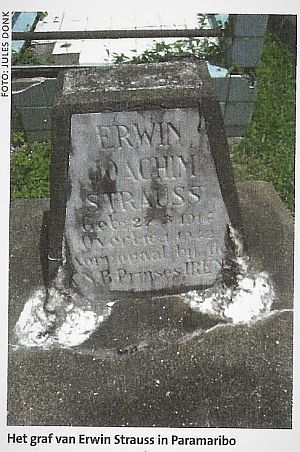

Harry Vos: Voss

Leo Alvares: Alvarez

Willem M. Burgzorg: Jacques Burgzorg; his date of death is nog 19/11/1946 but 19/11/1945

Jozef N. Rodriquez: Rodriguez

Anne D. Bosschart: Anne A. (Anne Anton)

Abraham S. Fernandes probably is the same person as Samuel F. Abraham

- With KNSM:

A.J.H. Askel: Aksel

A.W.I. Naardendorp: Naarendorp

W.H. Beelds: Beeldstroo

R.C.Colader: Rolader

H.H. Exel: van Exzel

I.P. Flu: J.P.

J.D.L. Wikkeling: J.L.D.

With thanks to Volkert Laurens Laan who provided the information about the monument and to William Man A Hing for corrections.

Anton de Kom

Picture: netherlands.indymedia.org

KOM, Cornelis Gerhard Anton de (known as: Anton, Antoine), the with communism sympathizing Surinam revolutionary and writer, was born in Paramaribo on 22 February 1898 and who died in camp Sandbostel near Bevern über Bremervõrde (Germany) on 24 April 1945. He was the son of Adolf Damon de Kom, small farmer and golddigger, and Judith Jacoba Dulder. On 6 January 1926 he married Petro nella Catharina Borsboom; together they had a daughter and three sons. Aliases: Adek, Adekom.

War

Two dark coloured camp prisoners from Neuengamme clear out debris in Hamburg-Hammerbrook.

During the Second World War De Kom provided copy and information to the illegal CPN-magazine (Communist Party of the Netherlands) De Vonk and, being averse to any sectarism, to the same magazine with the same name from the International Socialist Movement. Tom Rot from the latter magazine valued De Kom for his contacts with a group, which deliberated about the future of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. On 7 August 1944 De Kom was arrested on the streets. At his home pamphlets and a crystal receiver were confiscated. After a few days in Scheveningen prison, De Kom went on transport to camp Vught. He must have been considered a severe case, because of his solitary confinement in the bunker. On September 6 he went on transport to camp Oranienburg, later on to Neuengamme. There is a picture of camp prisoners in the inner city of Hamburg, with possibly De Kom on it (last of the dark coloured man in the back). The evacuation of this infamous camp eventually proved to be fatal. De Kom died on 24 April 1945. Only in 1960 his remains were identified and buried on the Loenen cemetery.

Source picture: www.kz-gedenkstaette-neuengamme.de

With thanks to John Brouwer de Koning.

Grave of Anton de Kom (picture: www.ogs.nl)

In 1982 he posthumously received the resistance remembrence cross. In the late sixties interest in De Kom and his work revived, also thanks to the detective work by his daughter Judith. Since 1983 the university of Suriname bares his name. On 24 November 1990 at the Anton de Kom-square in Amsterdam Zuidoost a plaque was unveiled by the artist Guillaume Lo A Njoe and on April 24, 2006 a bronze sculpture by artist Jikke van Loon.

On the 4th of May 2006 the Surinam governement attached a plaque to the war monument in Paramaribo. On it is the name of Anton de Kom as one of the 11 resistance fighters who died in the Netherlands (see below). Earlier, in 1986, a memorial was placed in front of the house of birth of Anton de Kom. The inscription says: Sranang / My Homeland / Once I hope / to see you back / On the day on which / all distress / will have ebbed away.

In remembrance of Anton de Kom, 22 February 1986.

Anton de Kom memorial, with Diana, occupant of the house of birth of A. de Kom

(picture: Pim Ligtvoet, 2007)

Youth

De Koms youth took place in a common neighbourhood in Paramaribo, Frimangron ('ground of the freed men'). Within this firm, catholic family De Kom stood out as being very studious. He read a lot and heard out the elderly about the time of slavery. His father still was born in slavery. The family name is derived from Mok, the plantation owners' name. After primary school and the Paulus secondary school, De Kom received his diploma in bookkeeping. He had a thorough knowledge of the English language, and a diploma in German, knowledge in French (conversation) and a sound knowledge of Surinam language of the people, Sranan Tongo, and of 'Negroe-English' and 'Papiamento', common languages on the Antilles. For four years he was an employee at the Balata Company 'Suriname' and 'Guyana'. On 29 July 1920 he resigned and left as a working passenger on a ship to Holland. For a year he served in The Hague at the Hussars, and then took a job as an assistant-bookkeeper. After being laid-off because of 'reorganization', until his departure for Suriname De Kom worked till the end of 1932 as a sales representative in coffee and tobacco. At his work and at the athletics field he was given many prizes, but he wouldn't take any insulting remarks about his color or about Suriname.

Political activities

About 1926 De Kom, who was by that time frequenting left wing and Indonesian-nationalistic circles, started to collect material for his book about the colonial history of Suriname, which would make him famous. In February 1927 he visited the foundation congress of the League against Imperialism and Colonial Oppression in Brussels. During the now following years De Kom developed towards the communist movement. Here he found a hearing, as shown by the Communist Guide of 4 May 1929, where 'our Surinam comrade Adek' in his speech urged 'that there will be searched for a connection between Indonesia and Suriname, because the power lies within the co-operation between the oppressed peoples'. Increasing political and journalist activities didn't keep De Kom from maintaining in contact with Surinam workers leaders like L.A.G. Doedel and Th.G. de Sanders. His article 'Terror in Suriname' in De Tribune (The Stand) 10 September 1932 was distributed in Suriname as a pamphlet. In it he criticized the prohibition of the just erected Surinam General Workers Organization (SAWO) and halving the wages of the Javanese contracters. He felt the slogan 'Suriname apart from Holland-now' among the Surinam proletariat was met with response.

Back to Suriname (January-May 1933)

De Kom's long cherished wish to return to Suriname, was strenghtened by his mother's illness. On arrival on 4 January 1933 an enthusiastic crowd awaited the De Kom family. Also the authorities, who were kept informed by the Dutch Central Intelligence Service, were at the ready. Three detectives kept an eye on him ever since. De Kom was shocked by the empoverishment in his country. He was denied having any public meetings. He therefore decided to start a consultancy firm in his father's yard. 'Maybe I'll succeed in taking away some of this discord which was the weakness of the coloured, maybe it won't be entirely impossible to make negroes and Hindostanis, Javanese and Indians, understand how only solidarity can unite all sons of mother Sranang in their battle for a decent human life.'

.

House of birth of Anton de Kom, A. de Komstreet (Frimangron)

Picture: Pim Ligtvoet, 2007

The rush to the De Kom's yard was, despite ongoing intimidation, unheard of. With interpreters they tried to keep the flood of contractors from speaking to De Kom. Among Javanese also was hope for De Kom helping them with their remigration. He firmly declined the offer from the maroons to provide him with weapons. 'For me it was all about organization, not a bloodbath.' This was exactly the danger to happen because of the provocative attitude from the police on 1 February. When De Kom demanded to speak to the governor, he was arrested. The writings from De Kom which were taken during house search, never showed up again. As an answer to the ongoing demonstrations the state of emergency was declared and on 7 February 1933 the surging crowd in front of the Office of the Public Prosecutor was dispersed with four salvo's. Two persons died and 22 were heavily injured (eight Creoles, eight Javanese and six Hindostanis). In Holland communist party member of parliament D. Wijnkoop plead in vain for De Kom to be set free, who to his knowledge 'never joined any communist organization'. Also he gave publicity to a nine items consisting political program circulating in Suriname. In it, apart from independence of state and nationalization of property abroad, another series of democratic and social demands were mentioned. On the 10th of May, after more than three months of imprisonment, De Kom was banned to Holland without any form of trial.

‘We slaves of Suriname’ (1933-1934)

Hundreds of workers, who were kept informed by 'De Tribune', welcomed the De Kom family in IJmuiden and Amsterdam. At the national congress of 'Links Richten' ('Aim left'), at the end of May, De Kom was welcomed with the 'International' song and chosen as an editor. By common assent the subscription was started to 'Wij slaven van Suriname'. Because of interference by the Dutch Intelligence the publication took place only as late as in 1934. In 'Wij slaven van Suriname' (Amsterdam 1934, 1971, 1972, 1975, 1986, 1999, 2003, 2005) De Kom rewrote Surinam history from the viewpoint of the oppressed. Fierce in its accusation, surprisingly personal in phrasing his convictions. 'It's taken a long time before I had myself freed from all obstacles in the obsession, that a negro always and unconditionally had to be inferior to any white.' Black self-consciousness, in his words self-respect and belief in proletarian unity, are central concepts. In the pre-publication 'Our heroes' in 'Links Richten' of May 1933 he held up as an example the around 1769 successful, but in history ignored freedom fighters Boni, Baron and Joli-Coeur to the Dutch proletarians: 'you, who aren't part of the debt of the oppressors, because you were oppressed yourselves, will love the advocates for our freedom and their portraits will be carried with you in your parades next to those of Lenin on the day, the huge balance with capitalism has been cleared'. This argument isn't mentioned in the book. Also A.S. de Leeuw pointed out, in his review in 'De Tribune' (1934.2.12), that the only logical conclusion - independence - is missing in the censured edition. How much has been taken out can not be checked anymore, because the original manuscript was lost during the war. Despite the efforts of E. du Perron no French translation was made, but a German version was published, translated by Augusta de Wit (Moscow 1935; Zürich 1936), and later on a Spanish translation (Havana 1981) and an English one (London 1987). Later on Jef Last gave the impression that he was the actual author of the book. The magazine 'Buiten de perken' refuted this in 1964-1965.

Appearances and articles

In the summer of 1933 De Kom wrote four articles about the situation in Suriname in üDe Tribuneü. It is well known from police reports he spoke at meeting from the Communist Party and the League. These reports also state he was in contact with the also shadowed Surinam Komintern-man Otto Huiswoud, editor of the European edition of The Negro Worker. In June 1934 De Kom supplied an article about Suriname for this magazine. Once he managed to read from his book for VARA-radio. This happened accompanied by music, but not without corrections in his text by order of the Radio Broadcast Supervision Committee. During speeches De Kom greatly impressed young communists, whom he met at an equal basis. One of them, Nico Wijnen, who worked with him illegally during the war, called him a born teacher: someone who gave himself too little credit because of his desire to help others, and someone who on the outside stayed calm and patient, but in fact was all nerves. Since his banishment from Surinam De Kom was unable to find a job. The family had to live on the dole. De Kom worked on at least two novels and at a film script. Only fragments survived. Later on a selection from his poems was compiled in Strijden ga ik (üBattle I willü, Leiden 1969).

More about ANTON DE KOM

Lou Lichtveld (Albert Helman)

Albert Helman in and H. Marsman behind the pram, about 1926 (Picture: www.dbnl.org)

Lodewijk Alphonsus Maria (Lou) Lichtveld (Paramaribo 1903-Amsterdam 1996), better known by his writers-name Albert Helman, descended from the coloured elite of Suriname. He was partly from Indian descent. As a twelve year old boy Lodewijk came to Holland for a study to become a priest (at the famous boarding school Rolduc, also small-seminarium of the diocese of Roermond). He soon quit his study and went back to Suriname. He attended a musical education and worked as an organ-player and composer. Albert Helman came back to Holland in 1922. Here he received an education as a teacher and he also studied music. After that he became a journalist and a music critic. He joined the group young Catholics of the magazine 'De Gemeenschap' (The Community). Later on he turned his back to Catholicism.

In 1926 he wrote, in the tradition of Multatuli, his first big work: South-West-South (1926). It deals with Suriname, which he glorifies, and about the negligence by the colonizer, Holland. His best known work, in this style, is 'De Stille Plantage' ('The quiet plantation', 1931). He would write a lot more novels, essays and poems. From 1932 until 1938 he lived in Spain. During the civil war he choose part (and fought with) the Republicans.

For the NRC and the Groene Amsterdammer (Dutch newspapers) he reported about the struggle for survival of the republic against fascism. After the defeat of the democrats (1938) at first he flees to North-Africa and Mexico, but by 1939 he is back in Holland. Now he is concerned about the fate of the German speaking Jewish refugees. By commission of the Committee on Special Jewish Interests he writes the book 'Millions-suffering'. Just before the war, during mobilization, he is invited to give a speech before soldiers in Gilze-Rijen, but this is prevented by high-ranking military authorities.

As Lichtveld was so well-known as an anti-fascist there was nothing else for him to do but to go into hiding. He falsified personal documents, published resistance verses and protested at Reichs Commisioner Seiss-Inquart against the foundation of the so-called Kulturkammer, of which artist where forced to become a member of. He wrote in the illegal magazine 'Vrije Kunstenaar' ('Free Artist') and was after the arrest of sculptor and resistance man Gerrit van der Veen in 1944 his successor at the editorial office. Lou Lichtveld also had contact with the Surinam resistance, probably also with Anton de Kom. During the Second World War he wrote also under other aliases like: Joost van den Vondel, Friedrich W. Nietzsche, Hypertonides, N. Slob and Nico Slob. He was a member of the 'Grote Raad van de Illegaliteit' ('Grand Council of Illegality').

Drawing by Jo Spier on the cover of 'Schakels', ed. Cabinet to the vice minister president, 1963 (www.surinaamsmuseum.net)

After the war he was a member of the Emergency Parliament and until 1961 had various political functions in Suriname, for example Minister of Education and Public Health from 1949-1951, chairman of the Auditors' Office and president of the Bureau Public Reading. The last years of his life he was almost blind. He kept writing at high-age, by the motto: 'An old cock makes a powerful bouillon'. Albert Helman died in 1996 in Amsterdam. It is harrowing on his death not even one publisher had an advertisement placed.

Hugo Pos

Hugo Pos (picture: www.verzetsmuseum.org)

Hugo Pos was born on 28 November 1913 in Paramaribo and died 11 November 2000 in Amsterdam. 'He was the second son of Coenraad Simon Pos, a prominent Surinam practitioner (locally trained lawyer) and magistrate. His mother Abigaël Morpurgo, came from a prominent Surinam family of printers. Though his grandfather on his fathers side was an orthodox Jew and his father chairman of the Jewish Church Council, he was brought up very liberally. He attended the Conradi school and when he was eight he went to the neutral Hendrik school. On his fourteenth he crossed the ocean to Holland. In Alkmaar he attended high school and then he engulfed himself in student life in Leiden to do his study of law in between booze and flirting, with an interruption of a few months in Paris, were he studied comparative law. At the capitulation of the Netherlands after the German invasion in 1949, Pos immediately tried to get away. The second attempt succeeded.'

He managed to get by boat via Delfzijl to Finland, where he was given a visa for Japan by the Russian consul. Eventually he ended up in England, where he trained to be an officer (boekenblog.blogspot.com). In 1941 he came into contact with the recruiting agency of the Dutch Legion in Canada. Pos went to Suriname and after a speech for 'Waakt Suriname' recruited 400 to 500 mostly Creole volunteers, who nearly all were dismissed. Minister H. van Boeyen did not want to take them in, presumably because of the white volunteers from South-Africa, who were preferred. Some of them persisted and were hired into the Princess Irene Brigade.

During the spring of 1942''he reported to the merchant navy as a Militiaman', according to Van Kempen. The merchant vessel 'Flora', his ship, was torpedoed, but he survived the adventure. He returned to Suriname, where he became a secretary to the Commission of the Militia. In 1943 he started as a civil employee to the Netherlands Civil Administration (NICA), who aided the Americans at the liberation of Indonesia. After the war he was sent on secondment as captain and military Judge Advocate General in Timor. He was also involved in the trials of Indonesian rebels, though he admitted later on having wrongly assessed the revolution and motives of the Indonesians (boekenblog.blogspot.com). 'Shortly after Pos was put in charge of the investigation on war crimes of the Japanese in neutral Portuguese Timor. In Tokyo and Yokohama he worked as a prosecutor at the International Court on minor war crimes'.

Three brothers Pos, all dentists, are on the list of Surinam Holocaust victims (see Surinam Jews).

'In 1948 Pos returned to Holland. For a short while he worked for the Netherlands Bank, the KLM and as a lawyer, but in 1950 again returned to Suriname, now being a registrar of decree, for jurisdiction. He became a judge and in 1960 attorney general. Already soon after his arrival in Suriname, he became a chairman of the theatre company Thalia. From 1961 unti 1965 he was a member of the Cultural Advisory Board for the Kingdom. He was part of the editorial office of Vox Guyanae and published by the name of Ernesto Albin in the magazine Soela.

In 1964 Pos returned for good to the Netherlands, where he brought new life to Caribiton, a foundation that tried to rouse cultural life among Surinamese and Antillean immigrants. He was part of the Sticusa Board (1965-1978), was until 1974 a member of the Amsterdam Court, until 1983 councilor and vice-president of the court of The Hague. After his retirement at the age of seventy he became the first chairman of the Country Bureau against Racism. He was in the Profession Board of the Literature Foundation, the Complaint Commission Participation of the city of Amsterdam and lectured at the School of Law. During the December murders in 1982 in Suriname, two of his former students Hoost and Riedewald died, which brought him to accepting the chairmanship of the Foundation for aid to the relatives of the victims of the December murders.'

Hugo Pos in 1998 (picture: R. Tjoe Ny)

After his retirement in 1985 Hugo Pos started to write out full. In 1995 his autobiography In Triplo was published. In 2006 his play 'The tears of Den Uyl' (1988) was performed in Holland and in Suriname. One of the actors was the later minister of development cooperation Koenders.

Principal source: Michiel van Kempen, administrator of the Pos' literature inheritance, on www.dbnl.org/tekst.

Hugo Desiré Ryhiner

Ryhiner was a captain in the KNIL and was in 1939 travelling from the Netherlands-Indies to Suriname.

KNIL-detachment at the Dam, on occasion of the re-burial of Van Heutsz (1927). Picture: www.wayneolivant.karoo.net

Because of the declaration of war by England and France to Germany, when it invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, the Netherlands, though neutral, also mobilized its troups. Ryhiner was assigned as an officer to a unit. This unit was ordered in the May-days of 1940 to stop the German advance to a dynamite depot in Overschie, north-west of Rotterdam. Already at the Willems Bridge across the Meuse it came to a fight. The high-command ordered them though to stop the bloodshed, although the Dutch weren't on the loosing side. The troups were taken prisoner of war. Hugo, the only one with a black skin, was threatened with kicks and got shot in the back. As by a wonder the shot was absorbed by his thick winter-coat, according to Tony Wong in his book on Surinam veterans of war.

Later during the war Ryhiner went into hiding and joined a resistance group from The Hague. He did courier work, distributed illegal newspapers like 'De Waarheid' (The Truth) and 'Je Maintiendrai' (I will maintain), and got hold of food coupons.

After betrayal he was arrested by the Sicherheitsdienst and imprisoned in Darmstadt. He did penal servitude on a broken railway. Because of the advancement of the Russian army early 1945 prisoners were being dragged from camp to camp. Hugo suffered from hunger oedema. With others he managed to escape. Together with other prisoners, forced laborers, civilians on the run and Nazis, they roamed to the American controlled area. They were met with distrust and put behind barbed wire, where they were left forgotten. In March 1945 he succeeded in getting on a transport to France. Via Belgium, in a badly fitting American uniform, he was back again in the country where he had been in 1939 for traveling on to Suriname.

Information from the website www.onderscheidingen.nl :

Rijhiner, Hugo Desire

Born in Paramaribo on 8 March 1905, died in the Military Hospital in Utrecht on 6 January 1991. olt d.Inf.KNIL (24-06-1939), btgw. etn.d.Inf.KNIL (25-01-1947 KB 12), res-kpt ML (16-10-1950), e.o. 01-01-1954. Knight 4th class of the Military Willems-Order; K.B. no. 41 of 26 June 1946. Under-lieutenant of the Infantry of the KNIL.

The Willems-order was awarded to him with the following motivation:

'Has distinguished himself during battle by excellent deeds of courage, tact and loyalty, by moving on forwards to the Germans with a constant and complete disregard of the heaviest enemy fire on the 12th of May 1940 at Overschie. He was able to inspire the few entrusted to his command, by which to the outnumbering, heavily and better armed enemy serious losses were sustained. When part of the reinforcements sent to him with an ensign (which part of it never had been under fire) hesitated, he managed, by giving himself the example, to make them go foreward. This all was done, despite the pains as a result from a ricochet-shot in one of his upper-legs, and his immense fatigue. When later on a part of his unit tried to flee, on behalf of his captain he took control again managed to assemble his men again, preventing anything worse.'

Harry Frederik Voss

Born in Paramaribo (Suriname) on 12 March 1912. Executed at Kota Tjane on 29 May 1943. Soldier with the infantry of the KNIL (30-10-1934), sergeant from 31 October 1940).

Known decorations: Knight 4th class of the Military Willems-Order (K.B. no. 45 of 8 August 1950; posthumously). On the plaque at the war monument in Paramaribo his name, spelled as Vos, is among the 12 military mentioned.

According to Ad van den Oord the Japanese invaders after their victory on 8 March 1942, wanted to make use in various ways of the captured Dutch military, including Voss. They wanted information, and also wanted them to train Indonesians for the Japanese army. Sergeant Voss, despite being tortured, refused any collaboration.

The motivation for awarding him the Military Willems-order also includes the equal treating of Indo-Europeans and Indonesians:

'Distinguished himself by committing excellent deeds of courage, tact and loyalty in the battle against the enemy, first as a prisoner of war in a camp at Lawe Segalagala (Atjeh), co-signing in May 1943 a petition with the request to withdraw the decision, in which Indo-Europeans were considered to be Indonesians and therefore had to serve as 'Heiho' soldiers in the Japanese army, and to decide otherwise to declare Indo-Europeans to be Dutch prisoners of war and as such being treated, which had the result that the signers of this petition were imprisoned by the incensed Japanese.

Further on by his persistent refusal to serve in the Japanese army, therefore being transported on 28 May 1943 to Kota Tjane in order to be executed, in full view of the entire population.

Further on, when a Japanese officer being impressed by his loyalty and firmness offered him a final favor, loudly proclaimed in Maleisian, so everyone was able to understand it: 'Japanese, I want a red-white-blue flag wrapped around my chest and then you can fire.'

Furthermore, when his wish was granted and he was granted another favor, let the Japanese know they were no fair soldiers, because they wanted him to betray his Queen; that they might think they had won the war, but the victory in the end would be to the allies and that, as long as there was only one Duychman alive, they would have no peace in this country.

Finally by, when the Japanese wanted to blindfold him, refused this in a courageous way with the words: 'I'm a Dutchman and not afraid to die', and, after having several shots already fired at him, still living, loudly called: 'Long live the Queen', until another shot ended his life, after which his body was thrown into the Alas river the next morning.'

Source: www.onderscheidingen.nl

Other military men and women (25)

Part of the war monument in Paramaribo (picture: Pim Ligtvoet)

Apart from the two decorated military men above (Ryhiner and Voss), an additional 10 persons are mentioned on the website. Also the names of the military persons on the plaque at the war monument in Paramaribo are added, as well as some members of the Princess Irene Brigade.