- Poem Govert Huyser: Men of ten years and older

- Decorated Netherlands Indies (letter A) and Mauretz Christiaan Kokkelink

- Indonesians in the Dutch Resistance against the German occupier

- Netherlands Indies under Japanese occupation (Occupation, Oppression, Consolation girls, Internment (incl. religious on Borneo)

- Netherlands Indies (gays)

- 15 August and the war in South-East Asia (Hans Liesker and Peter Slors)

- Commemoration speech of dr. Bernard Bot, minister of Foreign Affairs of the Kingdom of the Netherlands (The Hague, 15 August 2005)

- Commemoration speech of prof. dr. B. Smalhout (The Hague, 15 August 2004)

- A dark page in the 400 year history of relations between The Netherlands and Japan (Japanese emperor in The Netherlands)

Also see Verhalen (stories):

Han Bawits and WW II

Ronald Scholte on Nagasaki

Camp notes by prof.dr. I.J. Brugmans

Memories by Friar Angelus

Experiences during the war by Max Tauran

Witness Jacob Litamahuputty

Also see the Antilles for the Japanese attack in 1941-1942 (Jan Willen van den Belt and Jan Frederik Haayen).

Men of ten years and older

The heiho flogged with well aimed lashes

Ten year old boys behind an army truck.

By incomprehensible decree they were

declared a man - and men

don't belong with their mother anymore.

He was in line with in his one hand his teddybear

clenched around the one paw left

In the other hand a bag with in it

The final bit of sugar and some malaria pills.

His mother put it in at last

He forced back his tears

After all, he was a man now.

His mother prayed and intensily hoped

To once see him again.

At his birth she had

thought of such a nice name for him.

She, she died of malnutrition and malaria

Lacked the pills that saved his life.

He ended up in a Dutch contract pension

Cold, wet, uncomfortable and not so nice either

The hunger winter was more important in conversations

Than his story of his – cruel - departure.

About good and evil he always thought differently

All his relations broke down

Booze and drugs sometimes helped, for a moment avoiding reality.

His career failed over and over

The only thing he missed was his old, one-armed, soft teddybear.

From: 'Fragments, memories of a camp boy', by Govert Huyser (2005). Publication made possible by financial support from the Military Victims of War and Related Purposes Foundation.

General b.d. G.L.J. Huyser (Surabaya 1931) stayed during the war in the Japanese internment camps 'Darmo' in Surabaya, 'Karangpanas' in Semarang and in the boys camp 'Bangkong' in Semarang.

Decorated Netherlands Indies (letter A) and M.Ch. Kokkelink

Civilians and military men and women from different groups in the Netherlands Indies, who were decorated for their behaviour during the war (only letter A)

For detailed information and the persons with the letters B to Z see www.onderscheidingen.nl

Aalbertsberg, Gerard. Born in Malang on 17 Februari 1908. Died in The Hague 6 April 1978. Resistance Star East Asia 1942-1945, Resistance Commemorative Cross. Journalist

Abdoel Sakoer. Bronze Cross. Native servant, on board of the destroyer Hr.Ms. 'Piet Hein'

Abdullatif-Nji Raden [noble title] Enong Tjitjik, Mrs. Resistance Star East Asia 1942-1945. Civilian from Bandoeng

Adjoen (alias Pang Linggan). Bronze Lion. Native civilian, involved with the underground resistance in the Netherlands Indies

Adriani, Paulus Lambertus Grimmius. Born in Makasser on 17 January 1914. Died on board of the Hr.Ms. Hydroplane 'X29' near Soerabaia on 11 February 1942. Flyers Cross. Officer-pilot 2nd class Navy Aviation Service, on board of the Hr.Ms. Hydroplane 'X29'

Agerbeek, Jacques Rola. Born Batavia on 21 March 1880. Died in Koepang on 17 August 1942. Resistance Star East Asia 1942-1945. Capitain of Infantry-titulair ret. from the Royal Netherlands Indies Army, authority of the Home Guard

Akoeilia Torey. Bronze Cross. Native civilian, member of the resistance in the Netherlands Indies

Akolo. Bronze Cross. Ambon sergeant 2nd class from the Royal Netherlands Indies Army

Alan. Bronze Cross. Native kampong leader, member of the resistance in the Netherlands Indies

Aliet, Hendrik. Born in Paleleh, Makassar, on 20 August 1912. Died in Monrovia, Los Angeles in March 1983. Resistance Star East Asia 1942-1945. Soldier with the Coast Artillery of the Royal Netherlands Indies Army

Alstede, Paulus Simon. Born in Buitenzorg (Bogor, Java) on 20 June 1906. Died on board of the Hr.Ms. Cruiser 'Java' in the Java Sea on 27 February 1942. (also see Jan Frederik Haayen at The Netherlands Antilles). Bronze Cross, War Commemorating Cross, Officers Cross XV. Lieutenant-at-sea 1st class, navigation-officer on board of Hr.Ms. Cruiser 'Java'

Altman-de Moet, Mrs. Lena Cornelia (“Corrie”). Born in Malang on 1 September 1911. Died in Benidorm on 24 April 1996. Married on 11 June 1929 in Amsterdam to Friedrich Heinrich Altman. Divorced in Djakarta on 20 May 1952. Resistance Star East Asia 1942-1945. Civilian in Soerabaja

Amag Darminah. Resistance Star East Asia 1942-1945. Town head of the dessa Pengantap, district Geroeng, West-Lombok

Amag Lebih. Resistance Star East Asia 1942-1945. Town head of the dessa Bengkok, district Geroeng, West-Lombok

Amag Redam. Resistance Star East Asia 1942-1945. Town keeper of the dessa Pengantap, district Geroeng, West-Lombok

Amag Sibah. Resistance Star East Asia 1942-1945. Town head of the dessa Blangas, district Geroeng, West-Lombok

Amahorseja, M.B.. Bronze Cross. Sergeant-telegrapher of the Royal Navy

Amak. Cross of Merit. Servant, on board of the m.s. 'Madoera'

Amat. Bronze Cross. Native civilian, member of the resistance in the Netherlands Indies

Ament, Cornelus Carolus. Born in Paroendjaia, Java, on 29 March 1896. Executed in Batavia-Antjol on 23 September 1943. Resistance Star East Asia 1942-1945. Employee of the General Agricultural Syndicate

Aroen. Bronze Cross. Native inland boy, with the Submarine Service of the Royal Navy

Asbeck, Thomas Karel baron van. Born in Kedongdjati (Java) on 14 October 1899. Died in The Hague on 23 October 1966. Knight in the Order of the Dutch Lion, Officer in Order of Orange Nassau and many other decorations. Officer in the Order of Orange-Nassau owing to: “Under difficult and often dangerous conditions in a competant and tactical way commander of our Escort vessel ‘JAN VAN BRAKEL’ and before of our Minelayer ‘VAN MEERLANT’ during over three years. capitain-lieutenant-at-sea, commander of Hr.Ms. Escort vessel 'Jan van Brakel'

Asjes, eng. Dirk Lucas. Born in Soerabaja on 21 June 1911. Died in The Hague in February 1997. Military Willems Order, Knight in the Order of the Dutch Lion, Flyers Cross and many other decorations. Military Willems Order owing to: “Distinguished himself during battle by excellent deeds of courage, tact and loyalty by during the period from 27 February 1944 until 22 September 1944 taken part personally in an exemplary way in a large number of operational flights of the Netherlands Indies 18th Squadron bombers from Australia to the by the enemy occupied area in the South Moluccas, on Timor and Flores and on islands in the Banda Sea and the Arafoera Sea, as well as on New-Guinea...”

Ayal-Nahuwae, Costavina ("Coosje"). Born on 15 April 1926. Cross of Merit, Resistance Commemoration Cross, Honorary Token for Order and Peace, Mobilisation-War Cross, Badge Wounded. Civilian. Cross of Merit owing to: "Acted brave and very meritorious during many months of guerilla fights against the Japannese in the Vogelkop-area of New-Guinea, and sharing all dangers and hardships of the guerrilla-fighters."

Source: www.onderscheidingen.nl

Mauretz Christiaan Kokkelink

Born in Willem I (Netherlands-Indies) on 17 June 1913. Died in French-Guyana in August 1994. Temporary fuselier at the KNIL (26-03-1931), militian soldier KNIL (09-12-1941), milition sergeant KNIL (01-01-1944), temporary mil-aaoi KNIL (09-08-1945), e.o. 20-07-1950 KB K.310. Author of the book 'Wij vochten in het bos - de guerillastrijd op Nieuw-Guinea tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog' (We fought in the woods - the guerilla war in New-Guinea during World War II). Knight 4th class of the Military Willems-Order; K.B. no. 17 of 12 april 1945. Militia-sergeant of the KNIL.

The Willemsorder was awarded to him with the following motivation:

"Initially as an under-commander, later on as commander of a detachment starting 58 men strong, after the occupation of Manokwari at New-Guinea by the Japanese in March 1942, showed great courage, tactful actions, perseverance and capability. Whilst having moved to the inland during the Japanese occupation, despite indescribable problems and hardships, during 2½ years brought the largest possible damage to the enemy, therefore even forcing Japanese authorities to put a prize of 10.000 guilders and a large portion of rice and salt on his head and sending out a force of 1100 Japanese soldiers to destroy his guerilla-gang. Still weak and ill, after reporting himself back to the Dutch authorities, immediately offering himself again for very risky tasks."

N.B.: M.Ch. Kokkelink is added because of his high decoration

Source: www.onderscheidingen.nl

N.B.: Also see the Netherlands Indies born marine Frans Meeng (section Suriname, A group of marines from Suriname, the Antilles and Netherlands Indies). He received the War Remembrance Cross with buckle for 'Krijg ter Zee 1940-1945' (War at Sea).

Indonesians in the Dutch Resistance against the German occupier

During the first half of the twentieth century, several hundred native inhabitants of the then Dutch colony 'Netherlands Indies' lived in the Netherlands. In the handbook of Harry A. Poeze 'In the country of the ruler' (see Sources) they are called 'Indonesian'. This term from that standard work is taken over here, like a big part of the information below. As to the spelling of the names of the Indonesians involved, although the correct historic spelling is the Dutch one, for reasons of pronounciability we follow in this translation the English transcription, e.g. 'Sunito' for 'Soenito', and 'Putiray' for 'Poetiray'.

Most Indonesians came from Java, others from Sumatra, Ambon, other islands, some were Chinese. They were mainly seafarers, maid-servants ('babus'), servants, students and a few artist. During the thirties there were about 800 Indonesians in the Netherlands. Comparatively many of them became active in the resistance against the German occupier, mainly from their organizations, but also individually. Much is known about the, mostly noble, students. In total there were about 60 to 100 persons involved.

The Indische Vereeniging and the P.I.

Board Indische Vereeniging 1924 (Society). Moh. Hatta (standing 2nd left), Pamontjak (sitting 1st right) (Source: H. Poeze e.a. p.178)

In 1908 the students and artists founded the Indische Vereeniging (I.V.), which was mainly dedicated to meeting, culture and mutual aid. During that period also in the same way separate organizations for Chinese students started (Chung Wha Hui, or Chinezen-Vereniging Nederland, Chinese Society Netherlands), and also for Muslims, Christians, servants and seafarers. Because of the growing political movement for independency the Indische Vereeniging radicalized and in 1922 the society was called ‘Indonesische Vereeniging’ and from 1925, in the Javanese language, ‘Perhimpunan Indonesia’ (P.I.). The battle-cry was ‘Indonesia merdeka!’ – Indonesia free! The student of economics and later on president Mohammad Hatta was one of the chairs and Sutan Sjahrir, the later on prime minister of Indonesia, was a member of the board.

Rustam Effendi (Source: BWSA socialhistory.org) e.a. p.178)

At the end of the twenties the P.I. became part of the communist movement, also because only there they could find permanent support for a free homeland. This was also expressed by the position of the P.I. board member Rustam Effendi, who became in 1933 an M.P. for the Communist Party of the Netherlands. During that time both Hatta and Sjahrir were suspended as members.

Rupi

Many students were unhappy with this change of course. There was already a ban on members of the Perhimpunan Indonesia to become a civil servant, so many were involved in secret – therefore there are no pictures of the board. But for communists this ban was even stronger. An awkward position for those who aspired a colonial job in government later on. Thus in 1936 a new cultural and social society came about: Rupi. It's name in full meant: ‘Rukun Peladjar Indonesia’, Union of Indonesian Students. In the board were members of different islands, university cities and convictions together. Leiden was the centre, but there were also groups in The Hague, Amsterdam, Wageningen and other towns.

Rupi board 1940. Left to right sitting: Evy Putiray, Suripno, Daliluddin, Rozai Kusumasubrata. Standing: Rasomo Wujaningrat, Amir Hamzah, Maruto Darusman (Source: H. Poeze e.a. p.178)

Familiar names were Sunito (law), Darusman (Indology), Daliluddin (Atjeh, chemistry), Suripno (chemistry) and Evy Putiray (Moluccas, chemical analyst). The first four of them were, like many others, also member of the Perhimpunan Indonesia. From 1936-37 the P.I. mitigated its course and started to give priority to the combined battle against nazism and fascism. Aid campaigns were organized for China, which became victim of the Japanese aggression in 1937, and the organization participated in international peace meetings in Brussels, New York and Paris. The various societies were moving closer together anyway because of the threat of war. The second Cultural Conference which was organized by Rupi from 7-8 September 1940 in the Club House in Leiden, counted 119 participants, among them non-students.

Occupation

Because of the German occupation the Netherlands were cut off of its colonies as were the colonies from the Netherlands. From January 1941 Indonesia also became occupied, by Japan. Because of the wars the students had no more financial support from their families and they faced problems with rent, food and study costs. Universities, funds and authorities filled in, though usually only for basic needs. The Leiden Rupi Club House at the Hugo de Grootstraat 12, ‘Rumah Indonesia’, became a central address for support. There were meals for those who had coupons (or not), medical consulting hours, cultural shows and a society magazine.

Badan Perantaraan

At the second Cultural Conference six organizations decided to co-operate in Badan Perantaraan (Body of Mediation) platform. They were Rupi, the P.I., the Perkumpulan Islam (Islam Society), the Indonesische Christen Jongeren (I.C.J.) (Indonesian Christian Youth), the Kaum Muda Indonesia (Indonesische Jongeren, K.M.I.) (Indonesian Youth), founded for seafarers, and the Kaum Ibu Indonesia (Indonesische Moeders) (Indonesian Mothers), founded for babu's. Other groups possibly stayed out, because of the demand to recognize Indonesian nationalism.

Final Fest Ramadan ('Lebaran') in the house for female and male servants, ‘babu's’ and ‘djongo’s’, Persinggahan House, The Hague (1934). Far right: minister Rana Disasmita, deceased during the war (Source: H. Poeze e.a. p.178)

Victims

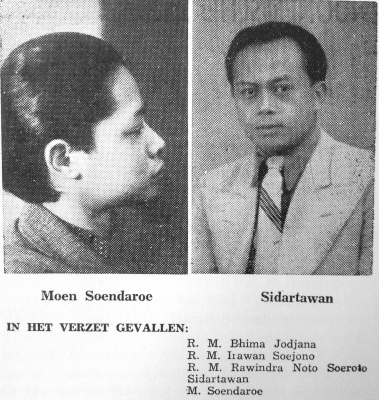

Many faced hard times. From the estimated 800 Indonesians in the Netherlands at least 86 died, over 10%. Most of them due to a combination of bad and uncommon food, severe cold and illnesses as tuberculosis. During the war the Perkumpulan Islam in The Hage buried 33 persons; during the first three years of war 14, during the last two years 19 persons. About the students from Leiden: in 1940 there were 39 Indonesians. Between May 1940 and the spring of 1944 12 of them had died. 8 of them of tuberculosis, whilst 7 of them were ill of the disease. Rupi chairman and student of law Purnomohadi died in April 1943 of an attack on a train, as well as Mrs. Sadjem from The Hague, three months later. The labourer Nitie Nardjam died in March 1944 because of a bombardment on The Hague. Eight other Indonesians died because of activities for the Resistance - one of them, Bhima Jodjana, because he studied in France and became a hostage of war. The last was Rawindra Notosuroto, who died in November 1945 because of the misery and tuberculosis he sustained earlier in a German correction prison.

From the P.I. magazine Indonesia, 15-1-1946 (Source: H. Poeze e.a. p. 329)

Resistance 1940-1944

Because of its communist course the Perhimpunan Indonesia was already used to illegal activities before the war. After the magazine ‘Indonesia’ had been prohibited the illegal 'Madjallah' (Magazine) was published from the Leiden Club House, followed in 1941 by a typed nameless leaflet. The P.I. was sufficiently in the centre of attention to, already in 1941, experience raids at its members in Leiden and Amsterdam. The doctor Parlindungan Lubis and the jurist Sidartawan Kartosudirdjo were arrested. The last one became the first victim of the P.I. He died on 15 October 1942 in Dachau. Lubis survived two Dutch and two German camps.

The organization was tightened. Next to chairman Setiadjit (‘Adjit’) Sugondo three others became leading members: Sunito, Suripno and Darusman, all with Dutch aliases. P.I. members were to follow orders by the leading members. How this went on, was told by Evy Putiray in her interview by Herman Keppy (2010). There was a structure of cells with five P.I. members each. One of them was in contact with the leading members and handed down the instructions. There were weekly meetings for training or a new assignment. There were student resistance groups in Leiden, Amsterdam, The Hague, Rotterdam-Delft, Utrecht and Wageningen. From mid 1942 there were even four sub-groups in Amsterdam. Leading members were Sianturi, Rasono Wurjaningrat, Ticoalu and Daliluddin. All members of the Perhimpunan Indonesia were in the Resistance this way. This usually also applied to their partners or fiancées.

Partners

The P.I. co-operated in the Resistance with the Islamic and Christian Indonesians, as before in the Badan Perantaraan. Evy Putiray was link with the Indonesian Christian Youth. With Sianturi, her later husband, she organized five I.C.J. conferences during the war, where everybody, also people in hiding and Dutch students, was welcome. A famous place was the conference center in Kerk-Avezaath (Tiel).

ICJ conference center Kerk-Avezaath. Left to right: Mr. Oey, Dora Maria Sigar (wife of Sumitro Djojohadikusumo), Moorianto Kusumo Utoyo, unknown, Estefanus Looho, Mrs. Olga Nelly Sigar (later wife of Estefanus Looho) and Jusuf Muda Dalam (Source: Facebook)

Evy tells in 2010 how big solidarity was, despite huge differences in religion or political views. There only was, she says, a difference with the student of economics Sumitro Djojohadikusomo, who admired Japan, ‘because we as P.I. believed Japan to be fascistic and a friend of nazi-Germany’. Still Sumitro helped the P.I. group in Rotterdam.

Dutch Resistance

The Perhimpunan Indonesia was also in contact with Dutch groups. In Amsterdam for instance with the illegal newspapers Vrij Nederland, Parool, Waarheid and De Vrije Katheder. One gave them information about the situation in Indonesia and supplied couriers. The last three papers were stencilled in the house of the family Susilo (Euterpestraat 167). And Setijadit was from the beginning editor of the student resistance magazine De Vrije Katheder.

Activities Rotterdam

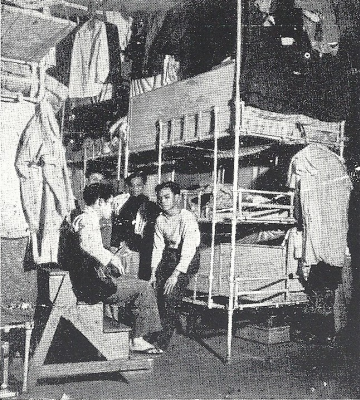

Indonesian seafares from 1946 (Javakade, Amsterdam) in a similar situation as their Lloyd colleagues between 1940-1945 (Source: H. Poeze e.a. p. 336)

The P.I. group of the Rotterdam students had a special character. The Handelshogeschool (Higher School of Trade) supplied during the entire war an allowance, which made surviving much easier. Also the harbour played an important role. Because during the days in May of 1940 66 Indonesian seafarers of the Koninklijke Rotterdamse Lloyd and the Maatschappij Nederland got grounded. They could not return. Material supplies by Lloyd were good, but the P.I. group, among them three children of doctor Pratomo from Djokja and a Dutch fiancée of one of them, were worried about a pro-German attitude and recruiting for the Arbeitseinsatz.

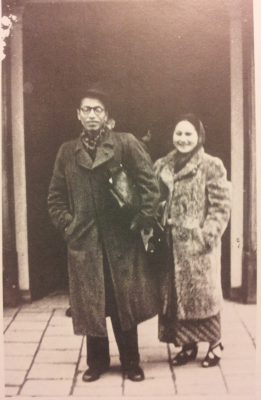

Stennie Gret and Djajeng Pratomo (ca. 1945) (Source: www.academia.edu)

The group also participated in the common Resistance, especially by the distribution of illegal pamphlets. After a while Djajeng Pratomo went living in The Hague because of safety issues. But there, after the arrest of his fiancée Stijntje Gret, he was arrested as well on 18 January 1943, together with housemate Mun Sundaru and two visiting labourers, Hamid and Kajat (see picture krontjong group Insulinde). The two students were sent to prisons and camps in the Netherlands and Germany. Mun Sundaru succombed in February 1945 in Neuengamme.

Delft and Utrecht

Two members of the P.I. in Delft were already in the common student Resistance and local illegal activities. After the protests against the discharge of three Jewish professors and two lecturers on 23 and 25 November 1940 they temporarily went into hiding. The Technical University was closed. The same, protests and closing, happened the week after in Leiden. In May 1942 Moorianto Kusumo Utoyo was sent to the Rotterdam group. Thahir Thajeb became that ill that he had to be admitted to hospital.

Homeopatic Hospital in Oudenrijn (ca. 1940-1948) (Source: www.hetutrechtsarchief.nl)

In Utrecht in the Homeopatic Hospital the room of a nurse, Djudju Sutanandika, became the centre of the P.I. Resistance. This hospital was located in the former Oudenrijn – nowadays the Kanaleneiland. In 1944 Djudju went to Wilhelminagasthuis (hospital) in Amsterdam where she continued her resistance work. In 1944-45 she worked as a carer and nurse with the fighter group of the P.I. in Leiden (Oegstgeest).

Leiden and Amsterdam

Also in these cities Indonesians and P.I. members participated in the common and students Resistance, for instance against the discharge of Jewish professors on 26 November 1940. Familiar names are Darusman, Hadiono Kusumo Utoyo and Suripno. The following closing of the University of Leiden was a blow. The future of the studies and the examinations became uncertain. A year later it became possible to continue studies in other towns. Most Indonesians then left for Amsterdam. Also the Club House moved there. They ended up in a building at the Willemsparkweg 194, where also a few students could live. In February, August and September 1943 several Indonesians were arrested in Amsterdam and temporarily detained, among them son and daughter Susilo. The stencil machine could be smuggled to the Club House. But because of tightened German regulations, later that year the building had to be closed.

Darsono and Alam Notosudirdjo ca. 1940 (Source: www.lowensteyn.com/indonesia/kommunis.html)

Darsono

Darsono Notosudirdjo, pupil of Henk Sneevliet and in 1924 one of the founders of the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI), went living in the Netherlands in 1933. Before that, during his stay in Moscow, he had broken with communism. Darsono did not join the P.I.. But during the war he was part of the Amsterdam Resistance, also as editor of the illegal weekly magazine ‘De Vlam’, founded by Jef Last.

The Hague

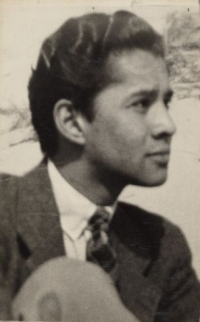

The very early resistance group of law student Rawindra Notosuroto, in The Hague and Leiden, also originated without connection to the Perhimpunan Indonesia. His father, Raden Mas Noto Suroto, was a well know poet and politician, who was at the cradle of the Indische Vereeniging in 1908. Already in July 1941 the group was completely rounded up and Rawindra survived the war only for a few months after over 2,5 years in a correction prison. He died in the Netherlands of neglected tuberculosis and weakening. His sister Dewatiah was also active in the Resistance, but had not been arrested. Their mother Jo Notosuroto-Meijer lived with the children in a part of The Hague that became 'Sperrgebiet' (forbidden area). Then she moved to Zeist. There she was caught because of her resistance activities and she ended up in camp Ravensbrück, which she survived.

Rawindra Notosuroto (ca. 1940) (Source: www.oranjehotel.nl)

‘Facts’

Another illegal group in The Hague, lead by the P.I., started at the end of May 1943, after the compulsary handing in of all radio sets, with a stencilled newspaper: ‘Facts’. In principle the one page bulletin was published daily. It started with the curious sentence: ‘From the information of the United Nations we derive the following’. For composition and printing they co-operated with colleagues from the Government Bureau of Metal Industry, where two of the Indonesians worked. Also the students were in Indonesian labourers, who co-operated as distributers, couriers or in other ways.

Arrests

On 3 April 1944, after treason, three editorial staff members were arrested: Muwalladi, Dradjat Durmukeswara and H. van den Bosch. Dradjat was important as a contact with the seafarers (K.M.I.), but not the leader who escaped. It was, together with technical draughtsman Van den Bosch, Ulam Simatupang. The names of the three other P.I. students had remained secret. They were the jurists Tamzil and Pamontjak, in the Netherlands since 1919, and the only Chinese member of the Perhimpunan Indonesia, the jurist Si Siu Giang. In August 1944 eventually four people of the network around 'Facts’ could be sentenced: Van den Bosch, a person in hiding who helped him with stencilling, Dradjat and a colleague from the Government Bureau, Hoenderop. Durmukeswara was sentenced to three years and sent to the correction prison Siegburg, which he survived.

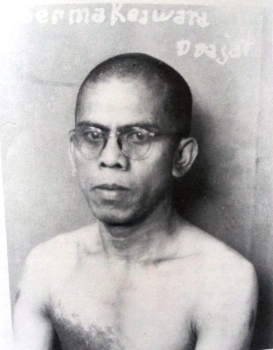

Dradjat Durmukeswara, registration Zuchthaus Siegburg 1944. (Source: Indische Letteren, jaargang 25 (2010), www.dbnl.nl)

Help to Jews and others in hiding

Here Pratomo and Keppy complement the story of Harry Poeze, who does not write about the help to Jews. Pratomo tells several units of the Perhimpunan Indonesia were intensively involved in helping Dutch Jews and Dutch people from the Resistance who were wanted by the nazis. They supplied, in Rotterdam, Delft, The Hague and Leiden, hiding places, food coupons and identity cards. Evy Putiray tells in her interview you just could be told to 'put away two Jews', which meant you had to find a hiding place for them where they were cared for’. In 1942-1943 Indonesians brought two groups of Jewish children from Amsterdam to a hiding place in the woods of the Veluwe and cared for them. Forty years on, by pure chance, one of the Indonesians met one of these children - who had become a doctor - that were taken into safety at that time. Could it have been Slamet Faiman or Rachmad Kusumobroto? Herman Keppy pays special attention to them on his website.

Rachmad Kusumobroto (1st left) with Nel v.d. Bergh (2nd right), Jewish children in hiding and others (1942) (Source: bd.yadvashem.org)

After the closing of the university, Leiden law student Rachmad Kusumobroto came into contact with the resistance work of his fiancée Petronella (Nel) van den Bergh. She worked in Utrecht at a shop owned by Jews, until this shop was taken over by a German ‘Verwalter’ ('trustee'). Nel helped Jewish children to go into hiding, among them the sisters Miri and Emi Freibrun. Rachmad helped her with this work. After a raid Nel was arrested and executed in February 1944 in camp Vught. The Freibrun girls survived, as well as Rachmad.

The Amsterdam P.I. member Slamet Faiman, trained as a seafarer and president of the K.M.I., also dedicated himself to Jewish and other people in hiding. Among them was the wife of fellow countryman L. Notohadinegoro-Brilleman. He looked for places for them, often with him at home in the Van Eeghenstraat 11, and forged papers. Also the Leiden student Irawan Sujono went into hiding with him. The polio he attracted during his illegal activities left him disabled for the rest of his life.

Keppy also mentions the name of Tole Madna (1898). He was not a member of the P.I.. Tole once came to the Netherlands as a foster child and lived with his babu Mina Saïna in The Hague. In 1942 Jewish Gitel Münzel came to ask for a hiding place for her nine months old son Alfred. Her husband and two older children were already under cover. The child stayed until the end of the war. Gitel survived Ravensbrück and found Alfred, as the only one of the family, alive with Tole and Mina.

The former Member of Parliament Nico Palar (SDAP) and his wife Joke Volmer can also be mentioned. Joke was already involved in spreading illegal papers and the distribution of coupons. Also their one-bedroom house in the Amsterdam Uiterwaardenstraat served a number of times as a temporary shelter for (Jewish) people in hiding.

Four military men

Viktor Louis Makatita (ca. 1939) (Spirce: www.hermankeppy.nl)

One of the four Indonesian cadets who started in 1939 their studies at the Royal Military Academie (KMA), Moluccan Victor Louis Makatita, was demobilised after the occupation. He was a free man and, unlike the others, not transported in 1942 as prisoner of war to Germany. In February 1942 Makatita, together with a KNIL colleague (Royal Netherlands Indies Army), tried to go to Switzerland or even the Netherlands Indies after that. Victor was arrested at the Swiss border and shot on 9 April in Dijon, together with two fellow-sufferers.

A second military person killed was also Moluccan, Eduard Alexander Latuperisa. He was a captain of the infantry of the KNIL in the Netherlands Indies and after arriving in 1939 in the Netherlands received a military staff function. After the occupation he became involved with the illegal 'Security Service' (O.D.), but was arrested in March 1942. Fifteen months later, on 29 July 1943, Latuperisa and sixteen other prisoners were shot at the Leusderheide.

The third military person who died during the war was non-commissioned officer Mas Sumitro. He lived with his wife in Soest and did not report himself during the occupation as German prisoner of war, but went into hiding. Sumitro then joined the Resistance, first in Soest, later on in The Hague. There, in the autumn of 1943, he jumped or fell out of a tram, and sustained such serious injuries that he died on 26 January 1944.

On his website Herman Keppy also mentions the Moluccan Wim Sihahainenia, who was in the battle of the Sea of Java (27 Febr. 1942). He was rescued and via Tjilitjap (Cilacap) and Colombo he ended up in Scotland, where he became a stoker aboard the O15, a Dutch submarine. There also people from Java and Menado (now Manado) served. Wim and his colleagues managed to get through the war unhurt. For sure there were more, unnamed Indonesians in the Dutch and Allied Forces.

Surviving

Apart from the support by universities and academies and the help via Rupi and similar organizations, there were different possibilities to get through the war. During the first years there still were ‘rice coupons’, but this came to an end because of poor supplies. Also the fuel allotments declined, while the winters were severe. All this resulted in students and labourers (the first mostly left wing and the last usually traditional islamic) who started living and working together. Until October 1943 the Ministry of Colonies payed Indonesians and Chinese - even though non-Aric - an allowance. Evy Putiray mentions an amount of 90 guilders a month, and speaks about it as 'bribe money'. Fiancées usually did not get married in order to keep the double allowance. At some point the allowances ended, presumably because of plans for forced labour in Germany, though the plans never fully were carried into effect. Students then had to try to get a job.

Colonial Institution

Krontjong group Insulinde (1941-1944). Front left to right: Moh. Jasin, Sugeng Notohadinegoro, Dradjat Durmakeswara. Back: Mustaman, Djajeng Pratomo, Hamid, Kayat, I.A. Mochtar, Untung Kasim (Source: Harry A. Poeze e.a., p. 313)

During the war the Colonial Institution, later known as the Royal Tropical Institute, offered financial support to Dutch colonials and Indonesian students. It also contracted Indonesian ensembles for dance, music, theatre and battle dances (pencak). They were mainly ‘Ardjoeno’ (1940) and ‘Insulinde’ (1941). Insulinde elaborated on the 'orchestra' of Indonesian seafarers (K.M.I.) and took in P.I. students as well. Also the social-democrat Palar, MP for the social-democrats (SDAP), played as a guitarist. The orchestra could perform in the Institute every fortnight on Sundays and was offered performances in other towns every month. The same applied to ‘Ardjuno’. In 1944 this ensemble was succeeded by ‘Bintang Mas’, for which the Colonial Institute contracted jurist and P.I. member Abdulmajid Djojoadhiningrat as an advisor. In August 1943, like Lillah Susilo and many others, he worked on a huge theatre production of the Institute in the Municipal Theatre, ‘De omgeslagen prauw’ ('The keeled over piragua'). The members of the Perhimpunan Indonesia poured the fees of the performances in the funds of the organization. So this was literally a ‘battle dance’. The Colonial Institute, though headquarters of the Gestapo, served as an illegal meeting place at the same time.

Lillah Susilo in 'De Omgeslagen Prauw' (Source: Harry A. Poeze e.a., p. 315)

East and West

This old organization for information about the Netherlands Indies and help for Dutch colonists and ‘inheemsen’ ('indigenous') (1899), became active during the war in several places for Indonesian students. Early 1942 former governor of the east coast of Sumatra, H. Ezerman (Arnhem), came to the aid of Rupi. Through him the meals in the Amsterdam Club House were funded. Former governor of Celebes, dr. L. Caron (Amsterdam), also came to the aid, with funds from the trade and industry. He distanced himself though from left wing ideas and actions against the occupier. Studying was the message.

Co-operation legally and illegally

Though of different opinions, the board members of the several committees for help to Indonesians knew each other well. The Indonesian community was small, some played and danced together with ‘Insulinde’. Members of the illegal Perhimpunan Indonesia therefore could do their resistance work without risk of treason and regularly used the social network of tolerated organizations like the Indonesian Christian Youth and the Perkumpulan Islam. This last one organized the major part of the Indonesians from The Hague.

Perkumpulan Islam The Hague

Kassanna accredits the oath at a marriage in city hall of The Hague (Source: H. Poeze e.a. p. 317)

During the years of war the centre of the Perkumpulan Islam was the house of chairman Kassanna (Obrechtstraat 220). The organization received help by students and graduates for their social and medical aid; these were persons like the doctors Abdulrachman (former Rupi), Murti Moerman and Sunarjo. Fund raising was done by jurist Zairin Zain (also former Rupi) and the economists Sumitro Djojohadikusumo and Saroso Wirodihardjo. This group of former students from Leiden and Rotterdam were in favour of independency for Indonesia, but kept themselves - contrary to the Islamic organization - out of German-Dutch affairs. In the social field they were pragmatic though. In the last year of the war Sumitro and Saroso helped the P.I. group Rotterdam to care for the seafarers at Lloyd.

Perhimpunan Islam The Hague

The P.I. group The Hague kept itself aloof from the Islamic Perkumpulan. Under the leadership of graduate jurist Suhunan Hamzah, and funded by Ezerman, they aimed for support of older Indonesian women. These usually were servants and they supplied them with butter, potatoes and clothing. The Perhimpunan was also involved in another project in The Hague: assessing requests for Indonesians and Chinese. For this the Leiden university invited jurist Kusna Puradiredja and also doctor Mohamed Ilderem, member of the P.I.. The committee Puradiredja actively encouraged these requests for support. From September 1944 it asked, supported too by East and West, the Dutch public to give Indonesian students hospitality and a meal. Which happened.

Others

Donald Putiray, with letter from Buchenwald (10-8-1944). Source: www.hermankeppy.nl

Collaboration

Apart from the attitudes of resistance, turning a blind eye on the support of it and complete non-intervention, there sometimes was collaboration with the Germans too. The best known example is the steward from Madura mr. Tumjati who worked for the Rotterdam Lloyd. Early 1941, after discharge by Lloyd, the Colonial Institute employed him as vendor and dancer. For a short time during that year he was a member of the NSB (Dutch nazi party), who quickly stroke him off as a member, as he was a coloured person. Early 1943, together with his Dutch fiancée, he founded an art ensemble, Sinar Laoet (Ray of the Sea). After some time the ensemble counted twenty persons from Java and Madura, and they performed Gamelan, Krontjong and Hawaiian music, as well as dance. The Colonial Institute considered the quality insufficient, but Tumjati was successfull. He regularly performed until the end of 1944, also for the NSB and in Germany.

Resistance 1944-1945

The last year of the war, during which the southern part of the country was already liberated, the railway strike paralysed parts of the country and the Hunger Winter began, was also a year of increasing resistance and relentless German repression. The Perhimpunan Indonesia undertook new illegal activities and did so often together with other groups.

Part of the Illegality

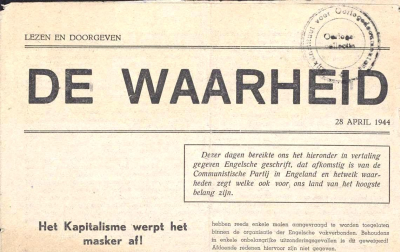

De Waarheid (the Truth) of 26 April 1944 (Source: geheugenvannederland.nl)

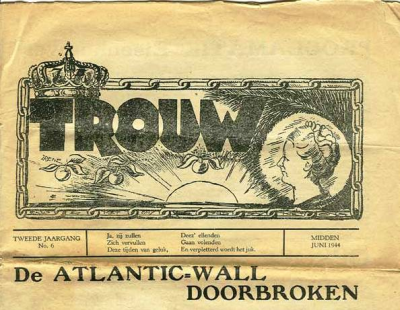

From the Amsterdam group Setiadjit, Suripno and Sunito talked to and wrote for illegal left wing newspapers, like the Vrije Katheder (Free Chair) and the Waarheid (Truth). They also stencilled these for three to four months. The Indonesian received typed stencils of De Waarheid on the street and printed the copy in a house in the south of Amsterdam. Then the papers were put in a suitcase and delivered at an address at the Stadionweg. The P.I. presumably was also in contact with the Resistance Board (RVV) and there were even connections with the - not very pro-Indonesian - Trouw (Faith) group. Eight students from Leiden trained with weights to be able to transport the type of Trouw without any obvious effort. The people of this ‘lead team’ were called the Amanullah’s - after a progressive emir from Afghanistan.

Trouw of mid June 1944 (Source: markt12.nl)

When on 4 July 1944 on desire of Queen Wilhelmina and the prime-minister the Grand Advisory Committee of Illegality (GAC) was set up, the Perhimpunan Indonesia became part of the left wing section and Setiadjit was their representative.

Female P.I. members

From the Amsterdam Wilhelmina Gasthuis (hospital) Djudju Sutanandika stayed in contact with Setiadjit. Through him she heard about a Resistance man who was sentenced to death and was in the isolation ward, where she happened to work. After his recovery from scarlet fever she managed to help him escape. The man probably was a member of the Resistance Board (RVV). Other women worked mainly as couriers because as men were sooner arrested because of the hunt for those who tried to escape the Arbeitseinsatz (forced labour). Familiar names are here: the jurist Tuti Sudjanadiwirja, Sutiasmi (Mimi) Sujono, the analyst Evy Putiray and student of law Trees Heyligers, fiancée of Sunito.

Tuti Sudjanadiwirja, Sutiasmi Sujono, Evy Putiray (Source: Harry Poeze e.a. p. 321)

Evy tells in the interview with Herman Keppy how she delivered illegal newspapers by train. When she travelled from The Hague to Haarlem and had to deliver something at a certain place, she went to the station early and searched for an empty carriage. There she put the package in an empty luggage net and then went to another part of the train herself. In Haarlem she waited until the train was almost empty, recovered the package and put it in her hand-bag. As ‘naive black girl’ she could pass the inspection. Which she did indeed.

Dutch P.I. member

In 1943 at the Colonial Institute Abdulmajid Djojoadhiningrat learned to know biology student Frits Bianchi. He happened to be a fierce proponent of Indonesian independency, also in discussions with acquaintances of Abdulmajid. To his surprise Frits was offered the P.I. membership by Sunito. He accepted the offer and also the corresponding discipline. This way Bianchi had a part in the Amsterdam Resistance work, from stencilling to training with weapons. Probably Trees Heyligers can also be considered as a member. After the war she defended 'Netherlands Indies-refusers' (Dutch military who refused to serve in the war against the Indonesians who fought for independence), like the well known Piet van Staveren and Zaandam citizen Arie Buth (1927-2010).

Liberation

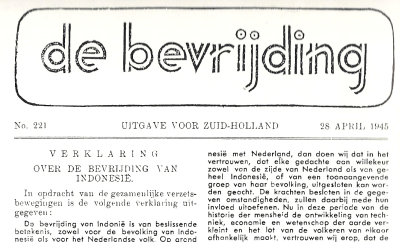

Also in Leiden the P.I. worked closely together with Dutch Resistance groups and illegal newspapers. Because of that they were, despite arrests in April 1944 around the paper ‘Facts’ (The Hague), able to publish a new paper in June, this time in Leiden. It had the provocative name ‘De Bevrijding’ (The Liberation) and contained mostly news messages. Nothing pointed to the Perhimpunan Indonesia being responsible for the publications, but veteran Pamontjak was the main editor. He was assisted by the editors Suripno and Harahap (vicar), and by Ticoalu, Irawan Sujono, I.A. Mochtar and Rozai Kusumasubrata, who organized the press and distribution. With help from the Leiden illegality the paper was stencilled. It was published three times a week in editions of 3,500, increasing to 20,000 towards the end of the war. This was enormous. Irawan, also named ‘Henk from The Liberation’, did the technical work: machines, paper, radio sets. During a raid on 13 January 1945 he fled by bike, but was lethally hit by a nazi bullet.

Illegal newspaper De Bevrijding, ed. 28 April 1945, about the liberation of Indonesia (Source: H. Poeze e.a. p. 326)

From September 1944 the newspaper also appeared in The Hague. Because of the railway strike it had become impossible for couriers to get the paper to other towns. The members of the 'Facts' group who were not arrested already were, together with Daliluddin, responsible for the editions. Sometimes the The Hague editors took over, by courier, editorials from the Leiden edition. They picked from the war messages themselves and sometimes wrote about Indonesia. The ‘Bevrijding’, made in The Hague, had only one page, was published three times a week to daily and had an edition of 4,000.

Also Rotterdam had its own edition. Again there was help from other Resistance groups for edition and distribution, but the editors were the economists Jusuf Mudadalam and Gondo Pratomo, brother of Djajeng Pratomo who had been arrested in 1943. The editors managed, with help from a Jewish man (in hiding) to make in a house in the Burgemeester Meineszlaan a radio listening post, by means of which the editors could have the latest information of the Allies. Gondo also managed to rent a house at the Aelbrechtskade, where a stencil machine was installed. With it the ‘De Bevrijding’ and later on the Rotterdam edition of the ‘Vrije Katheder’ could be printed, and also temporarily ‘De Waarheid’. Also here the main leaders of the P.I. could be welcomed. Sunito and Darusman came for discussions. Setiadjit went into hiding for a couple of months in the house.

Armed Resistance

In 2014 Djajeng Pratomo tells the following about the start of the Armed Resistance. The Rotterdam student of economics Jusuf Mudadalam was in a Dutch K.P. group, also known as knokploeg (strong-arm boys). In 1944 they made a successfull attack on a police post, where they managed to obtain four Walther pistols. Later the Indonesians in Rotterdam received more weapons via the Dutch Resistance, like two carbines, five pistols and ammunition. They came from German Wehrmacht soldiers who were in hiding with Dutch families, and who were fed up with the war. The Indonesians were trained by one of them, a ‘Gefreiter’ (lance corporal), trained how to use these weapons. Mudadalam also participated in an attack on a distribution office for food coupons in The Hague. The attack was done by bike and the action was a success. But at the meeting point the members were ambushed by the Germans. Jusuf managed to escape, with his machine gun and other weapons. Later on the Rotterdam P.I. group could retrieve with a carrier cycle nine jute bags with hand grenades, disassembled stenguns and ammunition at a Dutch Resistance man in the Watergeusstraat. The weapons came from droppings by the R.A.F.. So the P.I. was well supplied.

Jusuf Muda Dalam, minister and bank governor under Sukarno (1964) (Source: pekerjamuseum.blogspot.com)

Domestic Armed Forces (B.S.)

This umbrella organization of the armed resistance movement had a student branch in Leiden. This branch had been founded by Suripno and had four groups. One of them was made up by the Perhimpunan Indonesia. The group was named after the Indonesian hero Surapati and was lead by Ticoalu or ‘Theo’. The P.I. strongly valued to be part of the Dutch battle for freedom and provided ten members. At an armed liberation of the city their task would be to take and hold the Leiden railway station. Because of the German surrender it did not get that far.

The members partly came from other towns: Moorianto Kusumo Utuyo from Rotterdam, Rozai Kusumasubrata and Djalal Muchsin from Amsterdam. The P.I. often had experience with espionage and sabotage in the Knokploegen. Djajeng Pratomo tells how they managed to get the stock of weapons collected by the Rotterdam group with Mudadalam, past the German inspection posts, by bike, along stealthy roads to Leiden. The Indonesians trained in Leiden in one of the cellars of a wool and sheet factory. After the death of Irawan Sujono the group called itself ‘Irawan’, and like this they marched in the Liberation Parade.

Evy Putiray tells Herman Keppy she was sent by the movement to Oegstgeest (Leiden) shortly after the death of Sujono. There eight P.I. students were in hiding. Vicar Frits Harahap was one of them. They were in the Resistance and had the task to attack distribution offices and steal food coupons. So they were presumably members of the B.S. group. Evy was not a member - her fiancé, Sianturi, was in Amsterdam busy with weapon training though - and neither was nurse Djudju (‘Juju’) Sutanandika, who cared for food and nursing of the students. In Leiden Evy worked as a courier. After 9 p.m., at 'Sperrzeit' (curfew), she went outside with parcels full of copy from the illegal papers. Vrij Nederland, De Waarheid and Trouw. She had to deliver the copy at a secret printer. Irawan Sujono had just been shot with this kind of work.

Hunger Winter

Setiadjit and Elly Setiadjit-Sumokil (ca. 1943) (Source: H. Poeze e.a. p. 306)

Evy Putiray tells more about Oegstgeest. It was the heart of winter and everybody was hungry. Her trip had been together with five other students, on bikes without tires. The three boys peddled, the girls sat at the back. Elly Sumokil, Setjiadit's wife, had a child three months old, who she had brought to a niece in the het Wilhelmina Gasthuis. She insisted on coming with them to Leiden. Once they were there she went straight into the kitchen to express milk. Juju immediately said: ‘'don't throw it away!’ Because it was the only milk in Oegstgeest. And so the boys had twice a day a ‘kopie susu’, coffee with milk. Exchanged with ‘tukang susu’ (milk man) for sheets, said Juju. Until Elly was gone after a week. ‘Where has the milk gone’, asked the Resistance men. ‘Our cow is back in Amsterdam’, Juju said. They were startled, but Juju and Evy laughed.

Leiden

The leadership of the P.I. really valued being present in the Leiden area, which had declined because of the closing of the university. The B.S. group as well as the publication of ‘De Bevrijding’ fitted this vision. For both activities headquarters were in the house of main editor Pamontjak. There was a stencil machine, one listened to English broadcasts and people were assembled to receive military training in the cellar of a neighbouring wool factory. A second central place, also for other Resistance groups, was the house of Hadiono Kusumo Utoyo, brother of the B.S. member. He was engaged in hiding places, food distribution, forgery and aiding several illegal papers. In the attic he had a stencil machine. All traces of printing activities were meticulously removed every time; used 'masters' were burned. As a recognition for his role in the Resistance Hadiono was made a member of the temporary city council in May 1945.

Amsterdam

Amsterdam also knew a, smaller, Indonesian B.S. group, under the leadership of Sunito. Here they practiced, according to witness Pratomo, in a house at the Amstelkade where the fiancée of one of the students lived; presumably Trees Heyligers. In contrast to the Leiden group they had to abandon the actions just before the Liberation because they did not have enough manpower.

Sunito Djojowirono and Trees Heyligers on 15 Febr. 1945, their wedding day (Source: De Antifascist, Aug. 2008, www.afvn.nl)

Hunger trips

In Leiden the efforts of the Indonesian students and labourers from The Hague were coordinated to get food in the Hunger Winter. They went up as far as Den Helder (100 km) and were reasonably successfull. The Dutch were moved to compassion for the people from the warm Indies with their thin stature. Thus there was a boat drawn by hand to Leiden with a mere 7,500 kilo's of carrots. The canal was next to the railway, which was under fire by the Allies. Fortunately nobody was hurt and all carrots got to Leiden and, the other half, to The Hague.

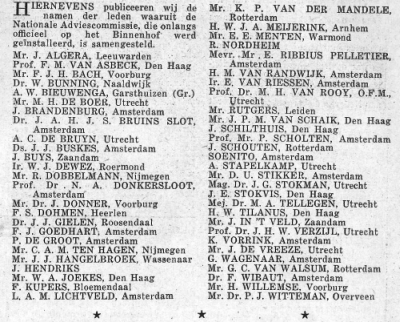

Soenito in the list of names of the Nationale Adviescommissie

(Source: Vrij Nederland 4-8-1945)

After the liberation

During the huge Liberation Parade of 8 May 1945 in Amsterdam also representatives of the Indonesian student organizations were present, while the P.I. was represented on the tribune by Setiadjit Sugondo, member of the Grand Advisory Committee of Illegality. Sunito Djojowirono became a member of the National Advisory Committee of the Former Resistance, which was in charge of filling in the free chairs in the Houses of Parliament. After 5 May the Leiden ‘Bevrijding’ revealed the newspaper had been published under the responsibility of Perhimpunan Indonesia. The paper published one extra edition ‘Welcome to our Allies’, with a summary of 5 fallen and 68 deceased Indonesians, and finally a manifest about how to achieve the independency of Indonesia.

Liberation Parade, Breestraat Leiden, with the Irawan group. The last to in the left row are Moorianto Kusumo Utoyo and Ticoalu (Source: H. Poeze e.a. p. 323)

Independency

This turned out to be achieved much harder and bloodier than was expected after the cooperation against nazi-Germany. It already had appeared so after the sudden death of Ario Adipati Sujono, father of Irawan, and minister in the war cabinet: his plead for independency met with no response; he died on 5 January 1943 in Londen of a heart attack. Several former Resistance members played an important role in the negotiations with the Netherlands - both parties often knew each other personally. After May 1945 there were also four Indonesians Member of Parliament, two pre-war: Effendi and Palar, and two new: Setiadjit and Pamontjak (First Chamber). Some of the Resistance fighters were executed in 1948 as unwelcome communists by the Republic, among them Setiadjit. Others were to have important posts in the Indonesian government after 1949.

Djajeng Pratomo cites at the end of his article about the Resistance Prof. Mr. R.P. Cleveringa, who initiated the heavy protests in Leiden in November 1941 after the dismissal of Jewish colleagues. At a remembrance assembly of 37 years Indonesian National Movement he said: ‘Where there was talk in the Netherlands about resistance, we did not have to ask: Where are the Indonesians. They were there and stood sentry. They made their sacrifices. They were in concentration camps, they were in prisons, they were everywhere...’(City Theatre Leiden, 25 May 1945).

Sources

- Harry A. Poeze, with contributions by Cees van Dijk and Inge van der Meulen, In het land van de overheerser, deel I, Indonesiërs in Nederland (1600-1950). (Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, KITLV, Dordrecht 1986), 398 p.

- Raden Mas Djajeng Djajang Pratomo, In dienst van de vrijheid. Uit: De rechten van het verzet, 1986, zie: http://javapost.nl/tag/djajeng-pratomo (15 feb. 2014)

- Herman Keppy, Nederlands-Indië tegen Duits-Nederland, op www.Hermankeppy.nl

- Herman Keppy, Interview with Evy Poetiray 14-2-2010, zie http://getuigenverhalen.nl

- Anonymous. ‘Eerst Nederland bevrijden, dan Indonesië’. Indonesische verzetsstrijders actief in Nederland tijdens Tweede Wereldoorlog. De Anti Fascist augustus 2008, p. 21-22, op www.afvn.nl

- Herman Burgers, De Garoeda en de Ooievaar. Van kolonie tot nationale staat. KITLV, Leiden 2011, p. 441

- Alam Darsono, Het zwijgen van de vader (Stichting Alam Darsono 2008). www.alamdarsono.nl/eigen%20activiteiten/homeeigen.html

- Jeroen van Driel, e-mail 13-12-2015; http://resources.huygens.knaw.nl/bwn1880-2000/lemmata/bwn5/palar; https://socialhistory.org/bwsa/biografie/palar

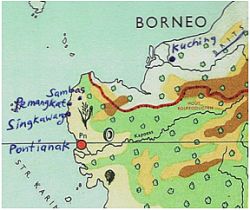

Netherlands Indies during Japanese occupation

Map: stuwww.uvt.nl

The capitulation of Japan on 15 August 1945 makes an end to what is called the Second World War. This capitulation was officially commemorated in Holland only in 1970, and only once. Up til then the attention had mostly been aimed at the events in the home country. Only an urn with soil from Indonesia was added in 1950 to the other urns in the monument at the Dam. From 1980 the 15-August commemoration has been held every year and since 1988 there is monument for the Dutch victims of the world war in Asia, the Indies monument in The Hague. The money for it was raised by the victims themselves. Also in other places, like Arnhem-Bronbeek, Roermond, Amstelveen and Den Helder monuments were erected or commemorations held. Finally in 1999 the date of 15 August was recognised as a historical day: the end of the Second World War. The last erected monument (Bronbeek, 17 August 2004) commemorates the thousands of victims from the Japanese prisoner transports at sea.

Occupation

The Japanese capitulation also made an end to the Japanese occupation of the former Netherlands Indies. After the attack of Japan on the American Navy Basis Pearl Harbor (Hawai) and the American declaration of war (8 December 1941) afterwards, the Japanese warfare extended from China to the Asian areas of British, Americans, Dutch and their allies. Parts of the Indonesian islands were already attacked in January and February 1942. On 27 February the battle of the Java Sea took place: under leadership of the Dutch admiral Karel Doorman the allied fought a desperate battle against the much better equipped and prepared Japanese (see also Surinam, KNIL). On 1 March 1942 the conquest of Java started, on 8 March the colonial authorities capitulated.

The occupation of the Netherlands Indies (by some 300,000 Japanese and Korean military men and civil servants) was welcomed by a part of the native population. The nationalistic part of the elite cooperated with Japan: it would bring independence from the Dutch yoke. Indeed the foundation for an independant country and army (‘Peta’) was layed. Others mistrusted the motives and methods of the Japanese occupation and were less enthousiastic. Especially Moluccans, Manadonese (Sulawesi) and Timorese actively resisted (see story Litamahaputty).

A talisman given by family, friends and acquaintances to a Japanese soldier. It is full of the names, with our without wishes and encouragements, from these people. The large text on the right hand side of the flag says: "In honour of Mr. Tirasaki Hiroharu" and next to it "Keep courage". Wished to him by Narita Kinjuro, who probably was the initiator. It is very likely Tirasaki Hiroharu has been a camp guard because the flag was taken by an ex-prisoner to Holland - www.museumverbindingsdienst.nl/leven3.html

Oppression

The major part of the 70 million inhabitants, ‘the people’, ‘rakyat’, was illiterate, and suffered increasingly under the occupation. Almost all men were put to work, usually a ‘force labourer’, ‘romusha’, or as aid soldier, ‘heiho’. Hundreds of thousands were deported to other parts of the archipel, to New Guinea, Birma, Siam, the Philippines or Japan. Many women were forced to become prostitutes, ‘consolation girls’ (‘yugun ianfu’) for the Japanese soldiers. Farmers were forced to deliver rice. The military police, ‘kempetai’, led a reign of terror in some places. The economic situation worsened. From 1945 there was a acute shortage of food and textiles.

Indonesian consolation girls

During the Japanese occupation of the Netherlands Indies about 20,000 Indonesian, Indo-European and also Dutch women were forced to act as prostitutes ('Consolation girls') for the Japanese soldiers. After the war their stories had to be kept secret for too long. Out of shame, out of the sexual charge. Or, in the case of Indonesian women, out of respect, because Japan helped the country to free itself and the independence fighters did not want to face the Japanese atrocities. Photographer Jan Banning (made ‘Sporen van oorlog: overlevenden van de Birma- en de Pakanbaroe-spoorweg’ ['Traces from the war: survivors of the Birma and the Pakanbaroe Railway']) and journalist Hilde Janssen therefore started in 2008 the project ‘Troostmeisjes in Indonesië’ ('Consolation girls in Indonesia'), a series of portraits, in pictures and in text, of the former forced prostitutes. In Indonesia twenty women are being interviewed extensively (oral history) and photographed. The portraits are recorded in a book and a traveling exposition (source: www.v-fonds.nl/pagina_202.html).

Wainem (picture: Jan Banning, text: Hilde Janssen)

Wainem, 1925, Mojogedang - Middle-Java, was taken from her home and forced to prostitution, first a year in Solo and afterwards in Yogyakarta. Together with other women in a hangar she was forced to weave mats and cook food during daytime. Sometimes they were raped on site, but usually soldiers took them to their room at the barracks. "Every week an Indonesian surgeon examinated us for pregnancy, while a Japanese soldier was watching. I never got pregnant during that time." After the war, together with a group of women, she walked about a hundred kilometers home. "Our people chased the Japanese out with bamboo spears. They grabbed everything we had: our rice, our money, our gold. In the evening when the air-raid alarm went off and we hid ourselves, the Japanese went into our houses and ransacked the place." She would rather not be reminded of what happened in that hangar. "That is such a long time ago. My son, who wasn't born yet, already has grandchildren." (source: http://nos.nl/artikel/152957-niet-mijn-bedoeling-deze-troostmeisjes-als-zielepoten-te-fotograferen.html).

Internment

The majority of the 300,000 Dutch and other Europeans in the colony, whites (‘totoks’) and coloured (‘Indo’s’), saw the Japanese occupation comparable to what the Germans had done in Holland. Some saw though that the colonial era was nearing its end or sympathised with the Indonesian strive for independence.

Like the Germans in Surinam and the Netherlands Antilles – often anti-nazi’s and jewish refugees – were imprisoned from May 1940 in internment camps (see there), and like Japanese civilians in the United States from 9 December 1941 were interned, this also happened to a part of the highly educated European top in the western colonies of Asia. Their fate was much worse though. About 16,800 of the 100,000 interned didn't live to see the end of the Japanese occupation, which is about a sixth of the camps population (see also article Liesker and Slors).

Compared tot the occupied British and French colonies the largest number of civilians were interned in the Netherlands Indies: about 100,000. 35,000 of them were younger than seventeen years. There were separate camps for women, where also the younger children stayed; and there were also boy camps.

Sub-camps for religious

Less known perhaps is that there were also sub-camps for religious, as for instance the camp Blitar on East-Java and in camp Kuching in the Maleisian part (Serawak) of Borneo. In this camp the religious on west-Borneo were interned. How did the war start in this region?

The Friars van Huijbergen

West-Borneo in 1941

In December 1941 the western district of Borneo has a new resident: A.S.L. Spoor. He mostly has to deal with two difficulties. First: the ongoing conflicts with the military and the civil servants.

The first friars leave for the Netherlands Indies on the ss Patria (1921). In front mgr. Bos is sitting, with next to him five Sisters of Veghel. Behind them are standing (with hat and under the small arrows) friars Leo Geers, Maternus Brouwers, Canisius van de Ven, Longinus van Spreeuwel and Serafinus van Tilborg

(Source: Huijbergen en de uiteinden der aarde)

Secondly there is a conflict with the mission which from the end of the 19th century on and under difficult circumstances, achieved a lot in medical and educational affairs. From 1919 this is done on instigation of pope Benedict XV, who writes that the missions can no longer restrict themselves to Christianization but have to consist, apart from a native church, also of schools and a small hospital. Many civil servants though see this as a state within a state and try to break its power.

War unlikely

At his inauguration Spoor is told by the local military commander Ter Poorten, that they are in a quiet district and that it is very unlikely that Pontianak (Kalimantan) will become part of the war zone. They feel safe with about 50 brigades, most of them being stationed at the 'secret airfield' of Singkawag II in the north (near the border with British Borneo). There large supplies of bombs, petrol for aircraft and food are stored.

The attack from the Japanese on Java starts on 1 March 1942. Other islands, like Borneo, are attacked much earlier, in some regions just after the bombing of 8 December 1941 on Pearl Harbour.

Pontianak bombed

The first air-raid alarm is on 11 December 1941; something inconceivable at the time. On 19 December bishop Van Valenberg says goodbye to the respresentatives of the mission, who he had assembled because of the outbreak of war. They return to their missions.

From the diary, written in stenography, of friar Bernulfus Bosman from Broeders van Huijbergen (Friars of Huijbergen):

“19 December 1941. The war starts here (Pontianak) devastating. While walking on the gallery of the school, we hear planes. There's no air-raid alarm. A bombardment on the Chinese quarters follows. The Dutch-Chinese school receives a direct-hit: the schoolrooms of the youngest are in ruins (the children were already sent home) and among the older students there are 15 dead. In town there are hundreds of victims and big fires. All friars work day and night to offer help. Pontianak becomes a dead town."

Dr. A. Heilbrunn, a German-jewish doctor and head of the mission hospital, estimates about 150 dead, 180 injured in hospital, minor injuries 50 to 75, died in hospital about 50.

Friar Emmanuel Compiet who works as a teacher in Singkawang writes that the news spread like wildfire and that almost all parents have taken their boys out of the boarding school. Save for about ten boys the school is empty now. The friar travels to Pontianak to assess the situation and is met by totally exhausted fellow-friars.

Kuching and Pemangkat

On 23 and 24 December the Japanese land near Kuching in Serawak and the threat is soon closing in. Also on 23 December the airfield is bombed. And on 25 December Kuching is taken by the Japanese.

During the night from 26 to 27 January news arrives that Japanese ships are spotted along the coast of Pemangkast. Destruction groups are installed to make sure nothing usable will fall into the hand of the Japanese. Von Uslar (see also the Sisters van Etten) is commander of the destruction group. The supplies of rice are distributed among the civilians and Von Uslar starts with the destruction of the rubber factories, cars, the stock of bear and petrol. This probably is the real reason why he will be executed by the Japanese later on.

All Europeans, among them friar Juvenalis of the mission in Sambas, and Von Uslar, are arrested.

Pontianak

In Singkawang friar Compiet writes that the assistent-resident proposes to meet the Japanese as a Red Cross team and being treated as such a group, in order to obtain better treatment. The group comprises of nuns, friars, some civilians and two civil servants with Red Cross-bands. They are arrested, but the nuns and a friar are sent back to their mission posts. Later on prisoners from Pemangkat and Sambas are added to the group.

"On 27 January 1943 the Japanese occupy Singkawang (about 100 km north of Pontianak). Two days later it's Pontianak turn. The friars get house arrest and barbed wire straight next to the house. We can't even get into the garden. All the time about four men are on guard. The friars house in Pontianak becomes more and more crowded, because all arrested inland civil servants are brought here. After a couple of months there are over 100 occupants in a friars house that used to be too small to accomodate 15 men.”

Kuching (at that time British Borneo, Serawak)

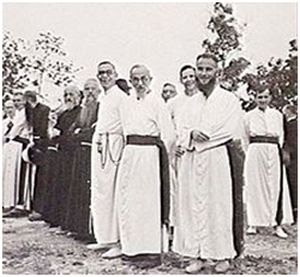

Camp Kuching (Source: Huijbergen en de uiteinden der aarde)

In July 1942 the friars from Singkawang and Pontianak (Kalimantan) are housed in a internment camp near Kuching (about 200 km north-east of Singkawang). The camp has almost 3,000 inhabitants, half of them die during the following years. The camp is devided into 10 sections, one of them a section of about 100 religious (also missionaries). The sisters and nuns are, not seperately, housed in the womens section. The camp inhabitants have to work hard: they have to enlarge the airfield and build roads, during which there's more and more shortage of food. Especially in 1945 many of the prisoners die of exhaustion, dysentery and hunger oedema.

Above: Drawing of Camp Kuching by friar Cornelis. On the drawing is written: "23 Huijberg friars. Connection between two barracks. Here we stood in line with 106 religious to have our plate filled".

Below: Camp Kuching with waving men just before their liberation.

(Source: Huijbergen en de uiteinden der aarde)

On 25 March 1945 a first sign of hope: during Mass high up in the air two shining American bombers fly over the camp. Everyone runs for the trenches but the bombers drop pamphlets. But camp life in Kuching still continues for almost half a year. On 11 September 1945 the survivors are liberated. Next the survivors can recover for some months on the island of Labuan at the coast of Brunei. The friars camp on the beach, 10 meters from the sea. The ones who suffered most, are in a field hospital to regain strength.

Already in December 1945 the School of Economics in Pontianak reopens (thanks to the help of many ex-students) and in January primary school starts again.

The story of friar Angelus van der Zanden about his experiences during the war in the prison in Kediri, the men's camp Tjimahi and the camp Blitar (Java) is elsewhere on this website.

1 dead, 1 badly injured

Eventually in 1946 friar Claudius Sommen still dies of dysentery because of the hardships in the camp. Friar Ireneus van de Avoird had a hard time during the rest of his life as resulte of the inhuman treatments he was given because he always stood out for his fellow-friars in the camp.

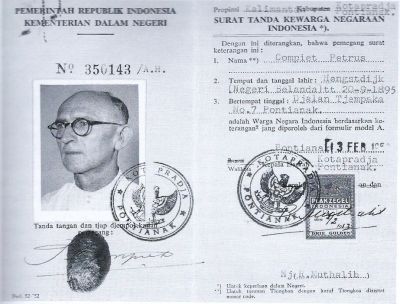

Indonesian passport of friar Petrus (Emmanuel) Compiet, 1951

(Source: Huijbergen en de uiteinden der aarde)

After 15 August 1945

After the liberation from the Japanese occupation the colonial Netherlands Indies heads for its downfall. The battle for independence is mainly fought on Java. The Broeders van Huijbergen on southern Borneo hardly notice anything. After the transfer of sovereignty in 1949 new rules apply. The official language becomes Bahasa Indonesia and other school books arrive. Finally the friars have to choose in December 1951 whether they want to have the Indonesian nationality. The ones who want to stay Dutch citizens, won't formally be able to teach after 1960. The bishop of Pontianak, mgr. Van Valenberg, advises all religious to ‘adapt to the people’, but gives everyone freedom of choice. Eventually half of the Broeders van Huijbergen accept Indonesian citizenship.

Note: The congregation of the Broeders van Huijbergen

The congregation of the ‘De Broeders van Huijbergen’ was founded in 1854 in the Brabant village of Huijbergen (Netherlands). From 1888 the emphasis was on ‘good education’ and within a few years friar primary and secondary schools appeared. Already in 1892 a private teacher college was founded.

In 1921 the first friars left for the Netherlands-Indies, the emphasis of the mission again with education. In Indonesia there are still friars of the congregation (2017).

Sources

War diary Borneo - Zusters van Etten (Sisters of Etten)

‘Borneo’, calender 2016, Bakker & Rusch, old school maps (‘Onze Aarde’ ca. 1950)

When the Broeders van Huijbergen from Pontianak arrive in Camp Kuching - also named Batu Lintang - on 16 July 1942, the Zusters van Etten have been there for three days. They are from the Sint Franciscus Convent in Sambas, not far from the border with British Borneo, and they have already been through a lot. This we know from their diary. It is an anonymus writing, as common in convents, but from the text two main authors can be derived: Sister Elisabeth and Mother Sophie. The writing itself, the temporary stop and the taking over by others, is a story in itself.

Picture of the community in 1939, during the visit of Mother Chantal from the mother convent in Etten. Some sisters from 1942 are not in the picture. Picture: Diary after p.16

Diary

On 3 July 1942 Sister Elisabeth (72) was told by Mother Sophie (63) to burn her notes, which she started in December. When discovered they would have been a threat to their safety. Ten days later, in Camp Kuching, the Mother regrets her decision and the Sister can start writing again “with courage and the help of my Guardian Angel”. She starts on 8 December 1941, and it seems very likely she recovered her former notes to do so. From the details she uses to describe the events during the former months, it is clear she did not burn the diary.

Marcus von Uslar

The danger of writing, referred to by Mother Sophie, is not an empty threat. The diary extensively presents the reason on 27 and 28 January, 17 June and on 2 July, the day prior to the order to burn it. Marcus Ernst von Uslar (Bern, 14-6-1903) is a Dutchman of Swiss descent and with whom the Sisters have a good contact. At the end of January 1942, together with inspector Bum, the priest and friar of Sambas and Father Kwadekker who is ill, he is run in by the occupiers and taken to the coastal town of Pemangkat. After a couple of days the last four are back, free. Meanwhile there has been a blaze in the center of Sambas, the ‘pasar’ (market), leaving thousands of people homeless. Five months later, on 17 June, Von Uslar is arrested again and thrown in jail. The Sisters and priest are already there for a month and witness his arrival. His mother, a Swiss citizen and subject of a neutral state, follows three days later, after a violent house search. Mother and son are not allowed to speak to each other in prison. During their stay and without their knowing (but the Sisters do hear so) their furnishing are flogged by the Japanese and more is to follow.

Part of the pasar (‘market’) of Sambas (ca 1928) Coll. wereldculturen RV-10771-36

Last hours

On 2 July, 20 armed soldiers arrive at the prison. They take a piece of rope from the Sisters, tie Marcus von Uslar up and pull him at the rope around his waist to the middle of the street. He is bareheaded and on bare feet and only wears his prison clothes: shorts. In front of him a piece of wood on a stick is carried, which says: 'This bad German burnt the pasar’. For three hours Von Uslar is dragged from kampong to kampong (neighbourhood) and across the market, and from there past the prison to the cemetery. He is not allowed to speak to his terrified mother. At the edge of a freshly digged grave he is shot. Fortunately Mrs Von Uslar does not hear the shots. She thinks her son is taken away to the harbour town of Singkawang.

But the Sisters do hear the shots and understand what happened from fellow-prisoners who had to close the grave. They can only think now that it is their turn. Secretly they go to confession with the priest, renew their monestic vows and listen to Mother Sophie who is reciting the prayer for the dying. But yet nothing happens. “ ...Our hour hadn't come yet.” Shortly after the Sisters are taken from their cells. On 13 July they are transported by boat to Malaysian Kuching, where a camp for Europeans has been opened.

Writing in Kuching

There Sister Elisabeth can take up the pen again, now the acute danger is over. In the pious and precise language of her generation Anna Catharina Swagemakers (Nieuw-Vossemeer, 14-6-1870) – thus were her secular personalia - describes the events in Sambas and the camp. Help from Above is also welcome without the incidents outside, because on 30 March 1941 she had a small heart attack at the monastery. The priest administered the last sacraments and it helped. Two years later, February 1943 in Kuching, the ilness makes it impossible for her to write. But the entries in the diary do not stop. Mother Sophie takes over writing until the end of August, when it becomes too dangerous again. After a pause until mid November another Sister, with big interruptions, continues the writing in the diary. Possibly it is Sister Floriberta who already before wrote a diary of her own. On 22 May 1945 her predecessor Sister Elisabeth dies. The diary of the Sisters ends on 22 July 1946 with parcels arrived in Sambas from many convents in The Netherlands. “Now we feel all one again.”

Book

The notes survive the occupation, emprisonment, camp, liberation and return to Sambas. Also the community in Pemangkat, possibly by Mother Eucharia, had written a short account of the events. It covers the first half year under Japanese occupation. Both documents are used to compile a little book with 144 densily printed pages: ‘De Zusters van Etten in gevangenschap en in het Concentratiekamp der Japanners op Borneo’. ('The Sisters of Etten in emprisonment and in the concentration camp of the Japanese on Borneo') Ninety pages are written by Sister Elisabeth. Below are eleven events whose description is based on the book.

1. The monastery expropriated

School, hospital and monastery Sambas. Picture: Diary, next to p. 33

Occupation

In Sambas, the capital of the Regency of the same name, the Sisters have their monastery, the 'Sister House'. From there they lead a school and a hospital. Both are being expropriated after the arrival of the 'Japs', on 27 January 1942. European men, also clergymen, are arrested, women and girls are threatened. Most Malaysians choose the Japanese side - though the sultan, Muhammad Ibrahim Shafiuddin II, workes against them - and some start looting.

Fortunately there is a Catholic among the Japanese officers. He makes Japanese inscriptions saying ‘no entry’ which the Sisters can stick to their temporary shelter in the woods. Early March 1942 all Sisters can return to their monastery, knowing none of their possessions will still be theirs. On behalf of the occupier the sultan declared that it all belongs to the Japanese army. Also the Sisters are not allowed to have any contact with the population, write letters of leave Sambas. Any violation will be answered with “being shot or head off” (p.16).

Father and workers in the rubber plantation Mission Sambas (ca. 1928). Picture: collectie.wereldculturen 10771-72

Japanese friends

After the nurses among the Sisters successfully treated a few sick 'Jap' soldiers in the hospital, and also the commander - called 'Whiskers' and 'Nicodemus’ by them - the attitude towards the nuns somewhat improves. And there is another Catholic among the Japanese, the guard Johannes. “16 March: ... Every day he walks over the concrete street to have a chance to greet Mother (Prior). One could see that they felt sorry for our tense lives". The feast-day of St. Joseph, patron of the mother house ‘Withof’ in Etten, is commemorated three days later with more confidence. (...) How would it be in occupied Holland. Would they be able in Withof to commemorate anything at all?’ (p.18).

Buddha

In April 1942 the Japanese staff have the Catholic church closed. The door is not nailed shut, because the church bell is needed. The priest is allowed to read Mass in the monastery's chapel. There the Sisters, like every year, renew their monastic vows. Mother Sophie, the prioress, forsees yet many problems. “If only we will stay together and be able to climb Golgotha Mountain [where Jesus was crucified, ed.] together", the nuns say. The joint continuation of the habits and rituals of the order will have to be their salvation. Shortly after, accross the church, a large Buddha statue on a throne is installed with an inscription which says: ‘Here lives the God of Sambas’. The author, like the priest who came to Borneo 'to save the souls from idolatry', sigh: “I do not believe any ordeal has struck and more deeply wounded our Father. But what can be done against an enemy like this?” (p. 23).

Working for the ‘Jap’